By Maria Sobotka

DE: Abb. 1 – Die kürbisförmige Kanne aus Seladon mit Lotosblütenmuster in kupferroter Unterglasurmalerei aus der Goryeo-Periode, ausgestellt im Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (links). Rechts ein chinesisches Stück mit einer ähnlichen Form aus dem Zhejiang/Yue-Ofen, datiert in die Nördliche Song-Dynastie, 10. Jahrhundert. Bild aufgenommen von der Autorin, 2020.

This gourd-shaped ewer stems from the Kingdom of Goryeo (918–1392). There are only three jugs of this type in the world. One is in the Leeum Samsung Museum of Art in Seoul, one in the Freer and Sackler Galleries in Washington, D.C. – National Museum of Asian Art, and one in the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (MK&G). What makes this piece outstanding is the fine underglaze painting in copper red. In the 13th century, the pigment cobalt was the first pigment that could be used to paint beautifully on porcelain, as many blue and white porcelains from China, Persia, and later Europe attest. What potters failed in for a long time, but the Koreans were among the first to succeed in, was underglaze painting with copper oxide. For the underglaze red painting, copper oxide is applied on the body before firing. It turns red afterwards. The difficulty in controlling the copper oxide pigment came with limited success and therefore resulted in a scarce use of this decor. This jug is special as it is one of the earliest and most delicate examples that we know of in this very technique. It is also extremely finely crafted: you can see that every vein of the leaves and even the small figurine on the edge of the ewer – a child holding a lotus flower – are extremely concise and elaborately rendered as is the beautifully shaped body of the jug with its sleek spout and handle.

DE: Abb. 2 – Die Seladon-Kanne im ursprünglichen Zustand, wie Justus Brinckmann sie erwarb und bevor sie im Leeum Samsung Museum of Art in Seoul restauriert worden ist. Archivmaterial. Copyright: Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg.

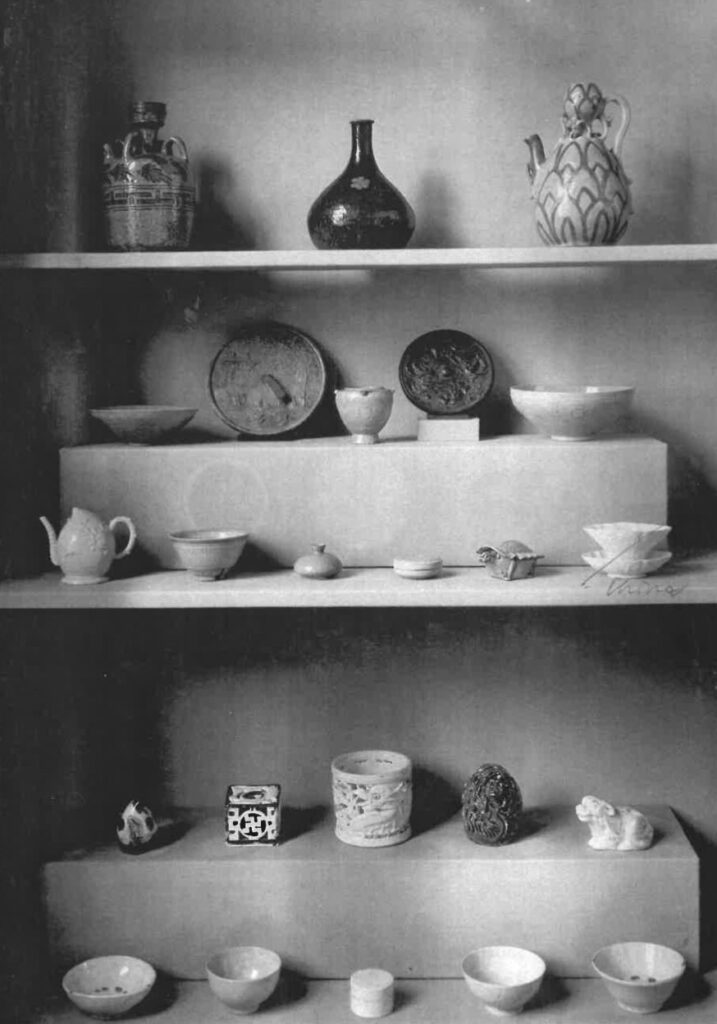

Justus Brinckmann (1843–1915) acquired this ewer from the Japanese art dealer Seisuke Ikeda (1839–1900) in Kyoto sometime before 1910. It underwent tremendous conservation treatment as you can see when you compare the current image with this historic photograph. The celadon ewer, located on the upper right, had been part of a display case during Brinckmann’s times as director. The jug in the Freer and Sackler Galleries was formerly owned by the collector Charles Lang Freer, who made a trip to Europe in the early 20th century and visited the MK&G in Hamburg. Perhaps he was inspired by Brinckmann’s purchase and somehow acquired a similar piece in the US?

References:

See Valenstein, Meech-Pekarik, and Jenkins, 1980 Oriental Ceramics, the World’s Greatest Collections: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Ohio State University: p. 179 for a description of this technique.

Other information stems from research that has been conducted between 2018 and 2020 in the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg by the author as part of the re-organization of the Korean gallery.

For further information:

The ewer is published in the Korean Collection at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg. Catalogue of Overseas Korean Cultural Heritage. No. 35. National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage (ed.), 2017, Samsung Moonhwa Printing Co. Ltd., p. 29-31.

See Nora von Achenbach, Die Botschaft der Dinge. Eine koreanische Seladonkanne mit kupferroter Bemalung im Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, in Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, Neue Serie; Nr. 35 – Frühjahr 2018, p. 9-14 for more information on the restoration process.

Diese kürbisförmige Kanne stammt aus der Goryeo-Periode (918-1392). Weltweit gibt es nur drei Kannen dieser Art. Eine befindet sich im Leeum Samsung Museum of Art in Seoul, eine in den Freer and Sackler Galleries in Washington, D.C. – National Museum of Asian Art, und eine im Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (MK&G). Das Besondere an diesen drei Objekten ist die feine Unterglasurmalerei in Kupferrot. Das Pigment Kobalt war im 13. Jahrhundert das erste Pigment, mit dem die Malerei auf Porzellan in ästhetisch ansprechender Weise ausgeführt werden konnte, wie viele blau-weiße Porzellane aus China, Persien und später Europa bezeugen. Was vielen Töpfern lange Zeit misslang, und wo koreanische Töpfer früh die ersten Erfolge verbuchen konnten, war die Unterglasurmalerei mit Kupferoxid. Bei der roten Unterglasurmalerei wird Kupferoxid vor dem Brennen auf den Scherben aufgetragen. Während des Brandes „färbt“ es sich rot. Die Schwierigkeit besteht darin, das Kupferoxidpigment im Brand zu kontrollieren. Der mäßige Erfolg vieler Töpfer führte darum zu einer seltenen Verwendung dieses Dekors. Diese Kanne ist besonders, denn sie ist eines der frühesten und feinsten Beispiele, die wir kennen, die in dieser Technik gearbeitet ist. Der Dekor ist äußerst fein gearbeitet: Man sieht nicht nur jede Blattader auf den sich nach oben verjüngenden Blättern des Lotos, sondern auch die kleine Figur am Rand der Kanne – ein Kind oder Mönch mit Lotosblume in den Händen haltend – ist überaus präzise und kunstvoll gearbeitet, ebenso wie der elegant geformte Körper der Kanne mit seiner schlanken Tülle und dem geschwungenen Henkel.

Justus Brinckmann (1843-1915) erwarb diese Kanne vor dem Jahre 1910 von dem japanischen Kunsthändler Seisuke Ikeda (1839-1900) in Kyoto. Sie wurde umfassend restauriert, wie man unschwer erkennen kann bei vergleichender Betrachtung des aktuellen Bildes mit der historischen Fotografie (Abb. 2). Die Seladon-Kanne ist hier oben rechts zu sehen in einer Vitrine, die vermutlich Justus Brinckmann selbst als Direktor des Museums einrichtete. Der Krug in den Freer and Sackler Galleries war früher im Besitz des Sammlers Charles Lang Freer, der Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts eine Europareise unternahm und das MK&G in Hamburg besuchte. Vielleicht ließ er sich von Brinckmanns Kauf inspirieren und erwarb in den USA ein ähnliches Stück?

Nachweise:

Siehe Valenstein, Meech-Pekarik und Jenkins, 1980 Oriental Ceramics, the World’s Greatest Collections: Das Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Ohio State University: S. 179 für eine Beschreibung dieser Technik.

Weitere Informationen stammen aus Recherchen, die die Autorin zwischen 2018 und 2020 im Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg im Rahmen der Neuinstallation der koreanischen Galerie durchgeführt hat.

Für weitere Informationen:

Die Kannen sind im Katalog zur Korea-Sammlung des MK&G publiziert, Korean Collection at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg. Catalogue of Overseas Korean Cultural Heritage. No. 35. National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage (Hrsg.), 2017, Samsung Moonhwa Printing Co. Ltd., S. 29-31.

Siehe Nora von Achenbach, Die Botschaft der Dinge. Eine koreanische Seladonkanne mit kupferroter Bemalung im Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, in Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, Neue Serie; Nr. 35 – Frühjahr 2018, S. 9-14 für weitere Informationen über den Restaurierungsprozess.