The online workshop “Between Tradition and Modernity: Korean Collections in Hungary and Germany” was hosted by ACN – Europe on 16 February 2023. The beginnings and developments of collecting Korean artefacts in these two European countries were outlined chronologically on the backdrop of the history of diplomatic ties, commercial networks and political changes.

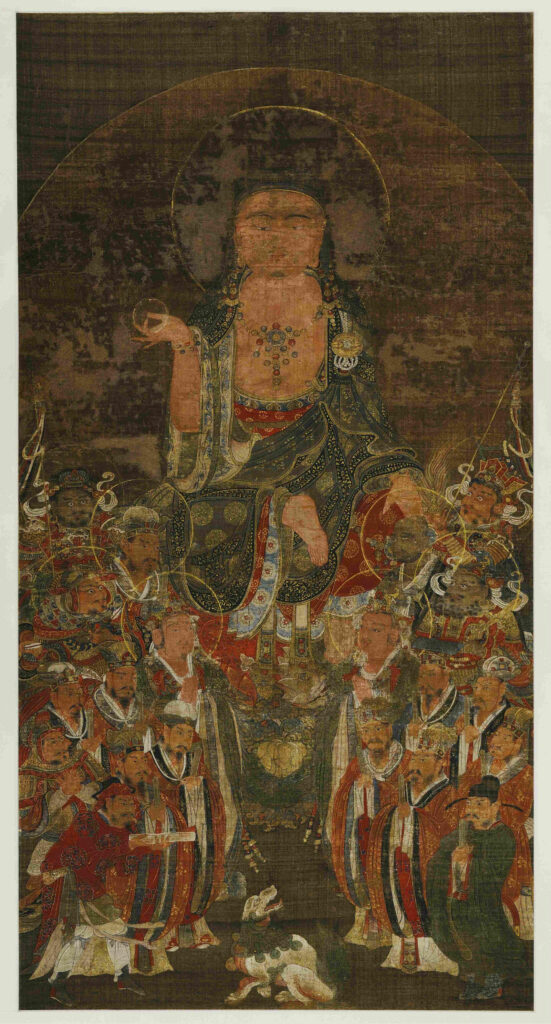

Maria Sobotka, curator for the Korean collections of the Ethnologisches Museum and Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, brought into the spotlight the main stages of the process of formation of Korean collections in Germany since the 19th century. She focused on a few individuals that had an essential role in the early purchase and acquisition of objects for German museums, such as the diplomat Paul Georg von Möllendorf (1847-1901) and the merchant and honorary consul H. C. Eduard Meyer (1841-1926). Her presentation highlighted how specimens of traditional Korean herbs and medicines entered German collections along with ceramics and bronzes, textiles and objects of everyday use. An important milestone also mentioned in the history of growing interest towards Korean culture was the first exhibition of Korean art held in 1894 at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe (Museum for Arts and Crafts) in Hamburg with the ensuing early publication on Korean art in German by the art historian Ernst Zimmermann (1902). One of the artefacts presented by Maria, a hanging scroll of the “Bodhisattva Jijang and the Ten Kings of Hell”, acquired in 1966 by the Museum für Asiatische Kunst in Berlin as Chinese and later proven to be Korean, gave the opportunity to touch upon a problem that in the past has at least partially hindered the study and understanding of Korean art, namely the confusion that caused certain pieces to be identified as Chinese or Japanese.

Beatrix Mecsi, Associate Professor and Head of the Department of Korean Studies at the Institute of East Asian Studies, Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE), Budapest, traced an outline of the most important phases and features of the arrival of Korean objects in Hungary from the early 20th century onwards. While a number of Hungarian institutions hold Korean artefacts, the focus of this presentation was on the Ferenc Hopp Museum of Asian Art in Budapest, which is the only museum in Hungary to be entirely dedicated to Asian arts and cultures. The villa and the core of the collections of this museum were donated to the State by the owner, the traveller and optician Ferenc Hopp in 1919. Beatrix pointed out that from the opening of the museum in 1923, the collection has been expanded from the original group of 4000 objects to the 30000 objects held today, 298 of which are Korean. In particular, she offered a detailed insight into: a group of life-size copies of the wall paintings of the Anak 3 tomb from Goguryeo produced by North Korean painters on commission from a Hungarian diplomat in North Korea in the 1950s; a rare portrait of a standing woman (Miindo) from the Joseon period, originally in the private collection of the renown Hungarian architect and designer Lajos Kozma (1844-1948), who might have purchased it in Paris after the occasion of the World Exposition in 1900. Of special interest was the analysis of the photographic collections including pictures taken and purchased by Ferenc Hopp and the naval doctor Dezső Bozóky during their stay in Korea in 1903 and in 1908 respectively.

The discussion following the presentations was started and led by Elmer Veldkamp, assistant professor of Korean Studies at Leiden University. While introducing his frame of reference as the Korean collections at the Museum Volkenkunde in Leiden, he explained the relevance of a comparison with the Dutch case based on the special commercial relationship between the Netherlands and Japan. In fact, the trade post in Dejima, Nagasaki, between 1641 and 1859 was instrumental in bringing Korean artefacts to Europe before other European counterparts. For example, the physician Philipp Franz von Siebold brought Korean objects to the ethnographic museum in Leiden already in 1837, quite earlier than the instances reported for Germany and Hungary. However, Elmer emphasised how, after the change in circumstances and loss of a privileged trade arrangement, the Dutch benefited from networks and connections with German collectors in further enriching their collections of Korean artefacts.

Among the main points of discussion, issues of cultural representations vigorously emerged. First of all, reflections were raised regarding the role of individuals especially in the decision-making of early collecting and in the establishment of perceptions of Korea in Europe according to sets of images and objects that became iconic. Secondly, it was highlighted that the peculiar political situation of a divided Korean peninsula since 1945 and the unbalanced international diplomatic relations also affect the way Korea is represented abroad. The recent exhibition “Uri Korea” at the Museum am Rothenbaum – Kulturen und Künste der Welt in Hamburg and the current exhibition “Hallyu! The Korean Wave” at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London were mentioned as examples of representations of Korea strongly influenced by the cultural trends of South Korea. Questions were therefore asked regarding the differences and similarities in the way the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in the North and the Republic of Korea in the South represent a Korean identity through the sharing of their material culture. In this respect, both the Hungarian and German case provide a good ground for comparison as their diplomatic ties with North Korea at certain times in their political history facilitated the acquisition of gifts from parts of the Korean cultural heritage that remain less accessible in other countries. In addition, as a more general remark, it was observed that the approach towards collecting Asian artefacts in Europe is intimately linked to how each European culture relates to Asia. This aspect stood out clearly when Beatrix explained the Hungarian traditional sense of cultural attachment towards Asia, where the Hungarian people see their origins, and the consequent effort to collect items from Asia that are not considered as curiosities but that help reinforce this cultural bond.