The House Model of a Daimyō Residence

Chinese Pigeon Whistles from the Slovene Ethnographic Museum

Rabab Pasisir in the Collection of the Asia and Pacific Museum in Warsaw

A Special Piece: a Celadon Gourd-shaped Ewer in Hamburg

Francisco Capelo, Portuguese Collector

East Asian Ceramics in Ivrea

by Marco Guglielminotti Trivel, Adjunct Professor of East Asian Art, Turin University. Former Curator and Former Director of MAO Museum of Oriental Art, Turin

Museum: Museo Civico Pier Alessandro Garda, Ivrea, Italy

Acknowledgements: Paola Mantovani (Director of Museo Civico P.A. Garda), Alessia Porpiglia and Luca Diotto (Museum staff). All images © Mariano Dallago. Courtesy of the Museo Civico P.A. Garda in Ivrea.

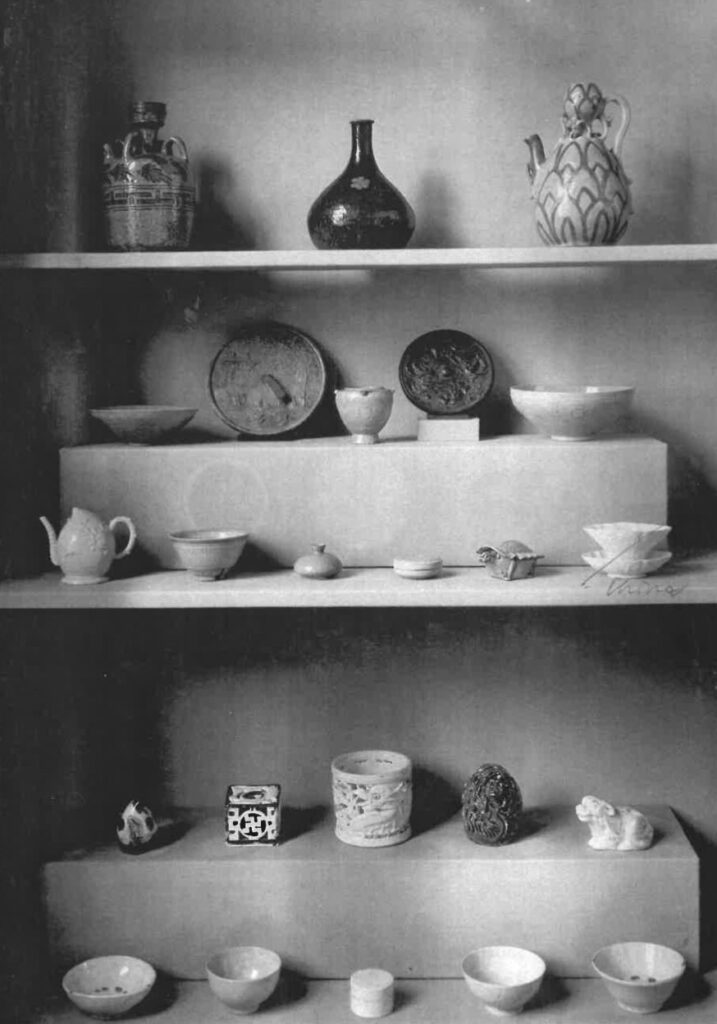

The Civic Museum of Ivrea, located in a major town within the Metropolitan City of Turin, houses an exceptional collection of hundreds of Asian artefacts, primarily Japanese and, to a lesser extent, Chinese. The majority date to the 18th and 19th centuries, with noteworthy examples of lacquerware and bronzes, some of which are outstanding. Less numerous and less studied are ceramics, paintings, and other materials.

The museum’s so-called ‘Oriental’ collection is historically significant and consists of two main groups of artefacts dating back to the 18th and 19th centuries respectively. These were acquired by two prominent citizens of Ivrea. Count Carlo Francesco Baldassarre Perrone (1718–1802) was a military officer and minister with a passion for collecting archaeological artefacts. During his diplomatic postings in Dresden and London, he assembled a collection that, in the late 18th century, became the basis of the so-called “Chinese Museum” at Palazzo Giusiana in Ivrea. This early museum included works from China, America, Madagascar, and India.

The second major figure is Pier Alessandro Garda (1791–1880), a Jacobin politician, revolutionary, and patriot who travelled extensively throughout Europe and South America, collecting predominantly Japanese works. In 1874, Garda donated his collection to the city of Ivrea to establish a museum, which is still named after him. Two years later, he purchased the Perrone collection and also donated it to the city. This combined acquisition formed the nucleus of the first “Japanese and Chinese Museum,” inaugurated at Palazzo Giusiana, with over 720 artefacts. Some additional Asian objects seem to have been incorporated into the museum’s collection by Garda himself before his death.

The collection’s significance lies in its precise terminus ad quem: 1880, the year by which all the objects can be confidently dated. However, its limitations include the difficulty of attributing individual pieces based on historical records and the near-total lack of documentation about their original acquisition. As a result, it is sometimes challenging to determine whether an item originally belonged to Perrone or Garda’s collection. Nonetheless, the collectors’ choice broadly reflects Perrone’s adherence to the 18th-century aesthetic of chinoiserie and Garda’s enthusiasm for 19th-century Japonisme.

In 2024, the Civic Museum hosted a temporary exhibition titled “In Praise of Fragility – Ceramic Art at the P.A. Garda Museum,” marking the 10th anniversary of the museum’s reopening after an extended closure, and coinciding also with the 150th anniversary of Garda’s donation of his Oriental collection. The most substantial section of the exhibition, enriched by national and international loans, focused on East Asia and was curated by the author of this post. The project provided an opportunity to revise some attributions of the museum’s ceramic holdings.

The collection includes about a hundred wares whose general characteristics align with the nature of their acquisitions, as previously noted during internal cataloguing projects: a clear dominance of export-oriented wares and Japanese artefacts (approximately 85%) over Chinese ones.

1.

Seated monkey holding a peach. Porcelain with

famille rose overglaze enamels, h 19 cm.

Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province. Qing Dynasty, 18th

century. Inv. no. 637,00.

Scimmia seduta con pesca. Porcellana a smalti

famille rose sopra vetrina, h 19 cm. Jingdezhen, Provincia del Jiangxi. Dinastia Qing, XVIII secolo. Inv. 637,00.

The Chinese objects are, on average, older, mostly from the 18th century, with a few 17th – and 19th -century exceptions. Highlights include blanc de Chine figurines from Dehua 德化 and famille rose

Canton porcelain 廣彩 – both highly sought after in European markets. There is also a miniature Yixing

宜興 teapot and several Jingdezhen 景德 porcelains with overglaze enamels, such as a polychrome figurine of a monkey nearly identical to a pair displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (accession no. FE.6A-1978).

The Japanese ceramics, predominantly from 1800 to 1875, consist mainly of Arita ware 有田焼 in the Imar伊万里 export style. Particularly striking are pairs of large vases and a large dish partially adorned with finely decorated lacquer. Other notable examples include brightly coloured Satsuma 薩摩 and Kutani wares 九谷焼, which were highly favoured by Europeans in the 19th century.

However, the collection also features ceramics less commonly sought after by European collectors. These include Banko wares 萬古焼 from present-day Mie Prefecture, with enamels often applied directly onto the biscuit, as exemplified by the teapot that is shown here. There are also two pieces of the Nanki Otokoyama 南紀男山 tradition, produced by the Sanrakuen kiln 三楽園焼 in Wakayama Prefecture. These feature thick glazes creating a raised effect, such as a bowl with decoration consistent with another example held at the Wakayama Prefectural Museum (id. 538).

2.

Pumpkin-shaped teapot. Stoneware painted with enamels on biscuit, h 8.5 cm. Yokkaichi, Banko ware.

Edo or Meiji period, c. 1825-1875. Inv. no. 452,00.

Teiera a forma di zucca. Grès dipinto a smalti su biscotto, h 8,5 cm. Yokkaichi, produzione Banko. Periodo Edo o Meiji, ca. 1825-1875. Inv. 452,00.

3.

Peony patterned bowl. Porcelain painted with overglaze enamels, d. 19.5 cm. Wakayama, Nanki Otokoyama ware. Edo or Meiji period, c. 1800-1875. Inv. no. 496,00.

Ciotola a motivi peonia. Porcellana dipinta a smalti sopra vetrina, d. 19,5 cm. Wakayama, produzione Nanki Otokoyama. Periodo Edo o Meiji, ca. 1800-1875. Inv. 496,00.

On the opposite end of the spectrum are two refined Hirado 平戸 porcelain pieces from Mikawachi, near Arita, delicately painted under or over the glaze. One standout is a dragon-boat-shaped incense burner, nearly identical to an example at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (accession no. 23.225.327a, b).

4.

Perfume burner in the shape of a dragon boat. Blue and white porcelain with golden highlights, 21.6 x 40.6 x 17.1 cm. Mikawachi, Hirado ware. Edo period, 1st half of the 19th century. Inv. no. 528,00.

Bruciaprofumi a forma di barca drago. Porcellana dipinta di blu sotto vetrina con lumeggiature dorate, 21,6 x 40,6 x 17,1 cm. Mikawachi, produzione Hirado. Periodo Edo, prima metà XIX secolo. Inv. 528,00.

Other wares are represented by only a single piece in the collection. These include a small cloisonné-decorated porcelain cup likely made in Nagoya, two impressed, unglazed porcelain dishes probably from Wakayama in the Kairakuen style 偕楽園焼, and a nice blue-and-white lidded bowl from Fukuoka Prefecture. This last item comes from the kilns of Sue 須恵焼 in Kasuya District, not to be confused with the sueki 須恵器 ceramics of ancient Japan.

5.

Small trays with a decorative character for ‘longevity’. Unglazed porcelain with moulded relief, 11.6 x 15.5 cm each. Wakayama, Kairakuen ware. Edo period, 1st half of the 19th century. Inv. no. 460,01 / 460,02.

Vaschette col carattere decorativo per “longevità”.

Porcellana non invetriata con rilievo stampato, 11,6 x 15,5 cm ciascuna. Wakayama, produzione Kairakuen. Periodo Edo, prima metà XIX secolo.

Inv. 460,01 / 460,02.

6.

Large bowl decorated with peonies. Blue and white porcelain, h 23.5 cm, d. 24.3 cm. Fukuoka, Sue ware.

Edo or Meiji period, c. 1800-1875. Inv. no. 242,00.

Grande ciotola decorata con peonie. Porcellana dipinta di blu sotto vetrina, h 23,5 cm, d. 24,3 cm. Fukuoka, produzione Sue. Periodo Edo o Meiji, ca. 1800-1875. Inv. 242,00.

Further research is needed to establish how and when these less common ceramics entered the museum’s holdings, potentially by identifying connections with similar artefacts dispersed across other European collections.

Bibliography:

Borriello, Maria Paola, Il Museo P.A. Garda. Cronaca e dibattito di fine ‘800, Tipografia Ferraro, Ivrea 1988.

Fragiacomo, Giuseppe, “Un esempio settecentesco di collezionismo in Canavese: il caso del conte Baldassarre Perrone di San Martino”, in Bollettino della Società piemontese di archeologia e belle arti, L, 1998, pp. 313-349.

Guglielminotti Trivel, Marco, “Consistenza e composizione della collezione di ceramiche orientali nel Museo Civico Pier Alessandro Garda / Consistency and composition of the collection of oriental ceramics in the Pier Alessandro Garda Civic Museum”, in Mantovani, Paola et al. (ed.), Elogio della fragilità – Arte ceramica al Museo P.A. Garda (In Praise of Fragility – Ceramic Art at the P.A. Garda Civic Museum), Sagep Editori, Genova 2024, pp. 32-33.

Harada, Kazutoshi – Koyama, Mayumi S. – Peternolli, Giovanni, Kinkô. I Bronzi orientali della collezione Garda, Hever Edizioni, Ivrea 2005.

Koyama, Mayumi S. – Vitali, Fabio A. (ed.), Lacche orientali della collezione Garda, Olivetti, Milano 1994.

Museo Civico Pier Alessandro Garda (ed.), Sezione orientale – Catalogo provvisorio, Rotary Club, Ivrea 1984.

Useful links

Asian collection at the City Museum, Ivrea (Italian only): https://museogardaivrea.promemoriagroup.com/collezione-orientale/

Pair of monkey figures: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1155162/figure-of-monkey-unknown/

Nanki Otokoyama bowl: https://wakayama.museum/hakubutu-wakayama/hakubutu-wakayama-538/

Perfume burner in the shape of a dragon boat: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45949

Ceramiche dell’Asia orientale a Ivrea

di Marco Guglielminotti Trivel, Professore a contratto di arte dell’Asia Orientale, Università di Torino, già conservatore e direttore del MAO Museo d’Arte Orientale, Torino

Museo: Museo Civico Pier Alessandro Garda, Ivrea, Italia

Ringraziamenti: Paola Mantovani (Direttore del Museo Civico P.A. Garda), Alessia Porpiglia e Luca Diotto (staff del Museo). Tutte le immagini © Mariano Dallago. Per gentile concessione del Museo Civico P.A. Garda di Ivrea.

Il Museo Civico di Ivrea, un importante comune situato nella Città Metropolitana di Torino, possiede una collezione pregevole di centinaia di oggetti asiatici, soprattutto giapponesi e in misura minore cinesi, quasi tutti risalenti al XVIII e XIX secolo: notevoli soprattutto le lacche e i bronzi, con alcuni pezzi eccezionali; meno numerose e meno studiate le ceramiche, le pitture e gli altri materiali.

La collezione del Museo, definita storicamente “orientale”, si compone di due nuclei principali, rispettivamente risalenti al ‘700 e all’800, acquisiti da due famosi cittadini eporediesi. Il conte Carlo Francesco Baldassarre Perrone (1718-1802) era un militare e un ministro, già collezionista di reperti archeologici, che ebbe incarichi diplomatici a Dresda e a Londra. Nella seconda metà del ‘700 aprì il cosiddetto “museo Chinese” presso Palazzo Giusiana a Ivrea, che comprendeva opere provenienti dalla Cina, dall’America, dal Madagascar e dall’India.

Pier Alessandro Garda (1791-1880) è stato invece un uomo politico di stampo giacobino, un rivoluzionario e un patriota che aveva vagato per tutta l’Europa e in Sud America, collezionando soprattutto opere giapponesi. Nel 1874 egli donò questa sua collezione alla Città di Ivrea con l’intento di aprire un museo, che in effetti è tuttora a lui intitolato. Due anni dopo acquistò anche la collezione Perrone per donarla alla città, che inaugurò così il primo “Museo Giapponese e Chinese” proprio in Palazzo Giusiana con un totale di oltre 720 oggetti. Qualche altro oggetto asiatico pare che sia stato accorpato alla collezione museale dal Garda stesso prima della morte.

L’importanza di questa collezione è quindi anche quella di avere un terminus ad quem preciso, corrispondente al 1880, per la datazione degli oggetti che la compongono. I limiti consistono invece nella complessa identificazione di un determinato oggetto in base agli archivi storici e nella mancanza pressoché totale di documentazione su dove e quando sia stato acquistato, per cui alle volte è persino difficile stabilire se pertiene originariamente alla raccolta di Perrone o a quella del Garda. Ad ogni buon conto, la scelta collezionistica obbedisce globalmente e pienamente ai canoni della chinoiserie settecentesca seguiti dal Perrone e alla passione per il japonisme ottocentesco abbracciata dal Garda.

Nel 2024 il Museo Civico ha realizzato una mostra temporanea dal titolo “Elogio della fragilità – Arte ceramica al Museo P.A. Garda”, dedicata ai 10 anni dalla riapertura del Museo dopo una prolungata chiusura e che corrisponde anche al 150° anniversario dalla donazione della collezione orientale del Garda. La sezione più consistente della mostra e la più ricca di prestiti nazionali e internazionali è stata sicuramente quella dedicata all’Asia orientale – curata da chi scrive – che ha costituito anche l’occasione per approfondire alcune attribuzioni delle ceramiche in possesso del Museo.

Si tratta di un centinaio di oggetti dalle caratteristiche generali che ci si poteva aspettare considerando la natura delle collezioni, quali erano già emerse nella schedatura interna al Museo: una netta preponderanza di produzioni per l’esportazione e degli oggetti giapponesi (ca. 85%) su quelli cinesi.

Gli oggetti cinesi sono mediamente più antichi, essendo centrati sul XVIII secolo con poche eccezioni seicentesche e ottocentesche. Soprattutto statuine blanc de Chine da Dehua 德化 e vasellame famille rose del tipo ‘porcellana di Canton’ 廣彩 – tra le produzioni più ricercate dal mercato europeo – ma anche una piccola teiera Yixing 宜興 e qualche porcellana dipinta a smalti sopravetrina da Jingdezhen 景德鎮. A titolo di esempio, una statuina policroma di scimmia che è quasi identica a una coppia esposta nel Victoria & Albert Museum a Londra (accession no. FE.6A-1978).

Per quanto riguarda la parte giapponese, che è per lo più databile tra il 1800 e il 1875, come c’era da aspettarsi la maggioranza delle ceramiche è di produzione Arita 有田焼 in stile Imari 伊万里 per l’esportazione. Spiccano su tutti delle coppie di grandi vasi e un grande piatto, parzialmente ricoperti di lacca finemente decorata. Bene attestate sono anche altre due produzioni caratterizzate da intense policromie che incontravano il favore degli europei nell’Ottocento: Satsuma 薩摩 e Kutani 九谷.

Eccezionalmente, anche qualche produzione meno nota che generalmente non era ricercata dai collezionisti europei trova posto nella collezione. Per esempio la Banko 萬古, prodotta nell’attuale prefettura di Mie, che è sovente smaltata direttamente sul biscotto come la teiera qui illustrata. Oppure la Nanki Otokoyama 南紀男山, prodotta nella prefettura di Wakayama dalla fornace Sanrakuen 三楽園焼, della quale si sono identificati due esemplari. Tali ceramiche sono invece completamente ricoperte di smalti spessi, che danno un effetto quasi a rilievo. La decorazione della ciotola è consistente con un’altra a fondo piatto conservata nel Museo della Prefettura di Wakayama (id. 538), seppure la forma e la tavolozza dei colori siano diverse. All’estremo opposto troviamo un paio di raffinate porcellane di tipo Hirado 平戸 da Mikawachi, presso Arita, dipinte delicatamente sotto e/o sopra vetrina. Identifico con tale produzione un bruciaprofumi a forma di “Barca Drago”, che troviamo quasi identico nelle collezioni del Metropolitan Museum of Art di New York (accession no. 23.225.327a, b).

Infine, altre produzioni sono rappresentate in collezione da un solo oggetto. Abbiamo un bicchierino di porcellana decorata esternamente a cloisonné, probabilmente prodotto a Nagoya; due vaschette da portata in porcellana non invetriata e decorata a stampo che provengono quasi sicuramente da Wakayama, in stile Kairakuen 偕楽園焼; una bella ciotola con coperchio di porcellana “bianca e blu” prodotta nella prefettura di Fukuoka. Quest’ultima proviene dalle fornaci di Sue 須恵焼, una cittadina nel distretto di Kasuya – da non confondersi con la tipologia ceramica sueki 須恵器 del Giappone antico.

Su come e quando tali ceramiche particolari siano pervenute nelle collezioni del Museo di Ivrea è un tema da approfondire, magari cercando connessioni con oggetti delle stesse produzioni “minori” sparse negli altri musei europei.

The House Model of a Daimyō Residence

by Dr Bettina Zorn, Weltmuseum, Wien

Museum: Weltmuseum Wien, Austria

Inventory No.: 117752

Name: Daimyō-Residence buke hinagata 武家雛形

Author: workshop Musashiya Masayuki

Place of Origin: Japan, Tokyo

Dating: Meiji Period, 1872

Material: wood, ceramic, metal, paper, pigments (ultramarine blue, gofun, mica) leaf gold, basalt, urushi lacquer, plant fibre, glass

Dimensions (cm): Height: 92; length: 462,3; width: 303

Images copyright © KHM-Museumsverband, Florian Rainer

One topic of the Vienna World Exhibition in 1873 was dedicated to architecture and Japan sent a series of architectural models, most of which are in the collection of Weltmuseum Wien. A central exhibit in the Japan Pavilion at the time was a unique model of a daimyō residence from the Edo period (1600 – 1868). It was shown under the category 19: “The bourgeois residence with its interior furnishings and decorations: realised buildings, models and drawings of residences of culture nations; fully furnished living quarters.”

In addition to the Roman numeral XIX, the paper label also bears the Japanese number 19. The model was built in 1872 by the Musashiya Masayuki model workshop in the district of Asakusa, Tōkyō.

Life in a residence, the second home of a daimyo, a high-ranking samurai in the capital Edo

The model shows only a few building elements of an overall residential complex that included many public and private buildings, gardens, a nō-theatre stage, etc. and provided accommodation for up to thousands of people: the daimyō’s family members, retainers, servants, etc. Strict rules of cohabitation and housekeeping applied. A fire watch tower in the model attracted interest at the World Exhibition in 1873 and its function was explained to visitors in the Vienna Fire Brigade Newspaper of June 15th.

The central, uncovered complex is a representative building. This is where a daimyo received his followers for political consultations and held banquets. The rooms could be enlarged or reduced in size according to space requirements. A kitchen area is located in the corner of the building. Food was served via aisles and covered corridors.

The roof remained uncovered due to the lack of time. A total of 10.000 ceramic roof tiles were used. The model has a Nō-theatre with a stage, walkway, the so-called bridge and the mirror room. This is where the spiritual transformation of the actor takes place through meditation in his role.

The collection of Weltmuseum Wien also includes models of a farmhouse, a barn, and a warehouse built by the same workshop.

Museum: Weltmuseum Wien, Österreich

Inventarnummer: 117752

Name des Objekts: Hausmodell einer Daimyō-Residenz buke hinagata 武家雛形

Hersteller: Modellbauwerkstätte Musashiya Masayuki

Ort: Japan, Tokyo

Datierung: Meiji-Periode, 1872

Material: Holz, Keramik, Metall, Pigmente (Ultramarinblau, Gofun, Glimmer),

Blattgold, Basaltstein, Urushi-Lack, Pflanzenfasern, Glas

Maße (cm): Höhe: 92; Länge: 462,3; Breite: 303

Lange Textversion: Ein Thema der Wiener Weltausstellung war der Architektur gewidmet und Japan schickte eine Reihe von Architekturmodellen, von denen die meisten sich in der Sammlung des Weltmuseum Wiens befinden. Ein zentrales Ausstellungsstück im damaligen Japan Pavillon stellt ein einzigartiges Modell einer Daimyō-Residenz der Edo-Periode (1600 – 1868) dar. Es wurde unter der Kategorie Gruppe 19 gezeigt: „Das bürgerliche Wohnhaus mit seiner inneren Einrichtung und Ausschmückung: ausgeführte Gebäude, Modelle und Zeichnungen des bürgerlichen Wohnhauses der Culturvölker; vollständig ausgestattete Wohngemächer.“ Neben der römischen Zahl XIX belegt das japanische Papieretikett an diesem Hausmodell die Nummer 19. Erbaut wurde es 1872 von der Modellbauwerkstätte Musashiya Masayuki im Bezirk Asakusa, Tōkyō.

Zum Leben in einer Residenz, dem Zweitwohnsitz eines Daimyō, eines hochrangigen Samurais in der Hauptstadt Edo

Das Modell zeigt nur wenige Gebäudeelemente eines Gesamtwohnkomplexes auf, der viele Bauten des öffentlichen und privaten Bereichs, Gärten, eine No-Theaterbühne, etc. umfasste und Unterkunft bot für tausende Menschen: Familienmitglieder des Daimyō, Gefolgsleute, seine Dienerschaft, usw. Es galten strikte Regeln des Zusammenlebens und der Haushaltsführung. Ein Feuerwachturm im Model erregte 1873 auf der Weltausstellung Interesse und seine Funktion wurde den Besuchern in der Wiener Feuerwehrzeitung vom 15. Juni erklärt. Der mittlere, ungedeckte Bereich stellt einen Repräsentationsbau dar. Hier empfing ein Daimyō seine Gefolgsleute zu politischen Beratungen, hier gab er Bankette. Die Räume konnten, je nach Platzbedarf, vergrößert oder verkleinert werden. Ein Küchenbereich befindet sich in einem Gebäudeeck. Über Gänge und überdachte Korridore wurde das Essen serviert. Das Dach blieb aus Zeitmangel ungedeckt. Insgesamt wurden 10.000 Dachziegel aus Keramik verwendet. Das Modell hat eine Nō-Theater mit Bühne, Steg, der sogenannten „Brücke“ und dem Spiegelraum. Hier findet die spirituelle Verwandlung des Schauspielers durch Meditation in seine Rolle statt.

In der Sammlung des Weltmuseum Wien befinden sich auch die Modelle eines Bauernhauses, einer Scheune und eines Lagerhauses, die von der gleichen Werkstätte gebaut wurden.

Bibliography:

Zorn, Bettina. ‚Die japanischen Hausmodelle der Weltausstellung 1873 in der Ostasien-Sammlung des Museums für Völkerkunde Wien’; in: Archiv für Völkerkunde, Bd. 53, 2003, Wien, 45-54.

Editor and entries about the House model Buke hinagata in the Museum’s magazine Archiv – Weltmuseum Wien, Vol. 65, 2015, Wien

„Hausmodell einer Daimyo-Residenz“, in: Weltmuseum Wien, Chr. Schicklgruber (Ed.), Vienna (German/Engl.), Wien, 2017, 284 – 285.

Quails and Mums

by Marta Logvyn (PhD student at the Scientific and Educational Institute of Philology of Taras Shevchenko Kyiv National University, leading research fellow of the Asian art department, the Khanenko Museum, Kyiv, Ukraine)

The author wishes to thank her fellow Ph.D. student Xiu Wei for his help in translating an inscription on a seal print

Author: Signed 馨園桂森 Xin Yuan Gui Sen

Title: A quail under a chrysanthemum bush

Dating: 1909 (?)

Materials: Ink and colors on silk

Dimensions: 82 х 43 cm

Place of Execution: China

Inventory number: 373 ЖВ

Museum: The Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko National Museum of Art, Kyiv, Ukraine

Chrysanthemums and a garden rock tower over a small bird. A small grasshopper sits on top of a garden rock. The whole picture is executed meticulously, in a decorative way. Even a seal print at the bottom right looks like a pebble in a garden, and this fact entertains us as much as the whole composition in the “birds and flowers” genre.

A painting was created at the time of the Mid-Autumn Festival. At first sight, it is imbued purely with auspicious symbols just suiting the occasion. Lush chrysanthemums are seasonal flowers. A chrysanthemum also stands for a talented “noble” person. Moreover, a chrysanthemum is a symbol of longevity since 菊花 júhuā for “chrysanthemum” sounds close to久jiǔ “long, permanent”.

A quail is a symbol of fecundity and peace since this bird lays lots of eggs, and “ānchún” 鵪鶉 for “quail” sounds close to “ān” 安 for “peace” and chūn 春 for “spring”.

Small insects like grasshoppers also symbolize fertility for the same reasons as quail: they breed fast and in high numbers. Yet there is another meaning in the picture. A perfect proportion of flowers and a stone slab to the size of the insect’s body seem to be like a mountain and a forest to a human. The very insect is depicted in a stage of a nymph, which is an intermediate stage in its development. The quail on the ground seems to notice the insect and it is ready to feast on it.

This way a peaceful scene becomes a scene of deep tension. We are left with open questions. Will the grasshopper escape the quail? Is it smart enough to hide in a maze of porous stone? Will it develop fully before the first chills of winter and will it be able to hibernate well into spring? We also can’t avoid a metaphorical projection of this scene into the human world.

At the same time, some linguistic material present in the painting has nothing to do with this idea of perils. Contrary to the pictorial metaphors, a seven-character inscription on the seal print in a shape of a pebble is quite carefree and hedonistic: 美人琴書共一船 “A beautiful lady, a cither, [and] books [are aboard] the same boat”. These words are a paraphrase of a quote from Bai Juyi’s poem 自喜 “Self-content”: 鶴與琴書共一船 literary “A crane is aboard on the same boat with books and a cither”. This quote became an idiom that stands for a tranquil attitude and satisfaction with life.

Considering all this layering of ideas in the same tableau I won’t be surprised if colleagues may discover and point out to more ideas imbued in this intricate piece!

The theme of “birds and flowers” painting and auspicious puns in the Chinese art is really vast. I would suggest two amazing sources, which are a book and an article:

- 焦俊梅.十二月花神. 湖南美术出版社 2011年156 页 ISBN 9787535644992

- Bai, Qianshen. “Image as Word: A Study of Rebus Play in Song Painting (960-1279).” Metropolitan Museum Journal, vol. 34, 1999, pp. 57–12.

Автор: Підписано 馨園桂森 Сінь Юань Ґвей Сень

Назва: Перепілка під кущем хризантеми

Час створення: 1909 (?)

Матеріали і техніки: Шовк, туш, водорозчинні фарби

Розмір: 82 х 43 см

Країна створення: Китай

Інвентарний номер: 373 ЖВ

Музей: Національний музей мистецтв імені Богдана та Варвари Ханенків, Київ, Україна

Дякую аспіранту Навчально-Наукового Інституту Філології КНУ імені Тараса Шевченка Сьов Вею за допомогу в перекладі напису на печатці

Над невеликою птахою височіють хризантеми та брила ажурного ландшафтного валуна. На вершині валуна сидить коник. Всю картину виконано ретельно, у декоративній манері. Навіть печатка внизу праворуч схожа на камінчик у саду, і цей факт нас розважає так само, як і вся композиція в жанрі «квіти і птахи».

Цю картину створено в час, коли відзначають Свято середини осені. На перший погляд, вона сповнена суто доброзичливими символами, які пасують святкуванню. Пишні хризантеми – сезонні квіти. Також хризантема символізує талановиту «благородну» людину. А ще хризантема є символом довголіття, адже слово 菊花 júhuā «хризантема» звучить подібно до久 jiǔ «тривалий; вічний» .

Перепілка є символом плідності та миру і весни, оскільки ця пташка несе багато яєць, а китайське слово “ānchún” 鵪鶉 «перепілка» звучить схоже на ān 安 «мир» та chūn 春 «весна». Дрібні комахи, як-от коники, означають плідність із тієї ж причини, що й перепілка: вони швидко розмножуються у великій кількості.

Проте в картині приховано й інший смисл. Ідеальна пропорція квітів та валуна до розміру тільця комахи подібна до пропорції гори і лісу до людського тіла. Саму комаху зображено в стадії німфи – проміжного етапу в її розвитку. А перепілка, здається, вже помітила комаху і готова нею поласувати.

Ось так у мирній сцені з’являється внутрішня напруга. Ми лишаємося із відкритими питаннями. Чи зуміє коник врятуватися від перепілки? Чи здогадається сховатися в лабіринті пористого каменю? Чи встигне повністю розвинутися до перших морозів і безпечно спати до весни? Врешті, ми не можемо уникнути метафоричної проекції цієї сцени на світ людей.

Одночасно певний мовний матеріал, присутній на картині, не має нічого спільного з темою небезпеки. На відміну від візуальних метафор, напис на печатці у формі камінчика, що складається з семи знаків, має досить безжурний і гедоністичний зміст: 美人琴書共一船 «Красуня, цитра і книги – всі в одному човні». Це змінена цитата з вірша Бай Дзюйї 自喜 «Самовдоволеність»: 鶴與琴書共一船, тобто «Журавель разом із цитрою та книгами – в одному човні». Рядок вірша став крилатою фразою, що перетворилася на фразеологізм, який позначає душевний спокій та задоволення життям.

Зважаючи на таке нашарування ідей в одному живописному творі, я не здивуюся, якщо колеги знайдуть і вкажуть мені на ще більше смислів, якими сповнена ця складна картина!

Марта Логвин, аспірантка Науково-Навчального Інститут Філології Київського Національного Університету імені Тараса Шевченка, провідна наукова співробітниця відділу мистецтв країн Азії Музею Ханенків, Київ, Україна

Тема жанру «квіти і птахи» в китайському мистецтві надзвичайно широка. Я б порадила два захопливих джерела: книгу і статтю

- 焦俊梅.十二月花神. 湖南美术出版社 2011年156 页 ISBN 9787535644992

- Bai, Qianshen. “Image as Word: A Study of Rebus Play in Song Painting (960-1279).” Metropolitan Museum Journal, vol. 34, 1999, pp. 57–12.

FUNERARY PROCESSION – Ming Miniature Figurines displayed at the MUSEUM of the Macau Scientific and Cultural Centre in Lisbon

by Elisabetta Colla, FLULisboa

Museum: Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau

Inventory No.:1538 to 1557

Name: Procession

Author: Unknown

Place of Execution: China

Dating: Ming dynasty (1368-1644) century AD

Material: Painted earthenware

Dimensions – from left to right (cm): 28 x 9 x 7; 29 x 10 x 7; 28 x 9,5 x 6,5; 28 x 10 x 7; 29 x 9,5 x 7; 28 x 9,5 x 7,5; 29 x 9 x 7; 29 x 9 x 7; 29 x 10 x 7,5; 29 x 10 x 7,5; 29 x 10 x 7,5; 29 x 10 x 7,5; 29 x 9,5 x 7; 30 x 9 x 7; 29 x 9 x 7; 29 x 9,5 x 7; 28,5 x 9 x 7;28 x 10 x 7; 29 x 9,6 x 7. Palanquin: 24 x 12 x 13,5.

These polychrome-glazed pottery figurines depict a miniature ensamble of a funerary procession. They belong to the permanent collection exhibited at the Museu do Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau (Macau Scientific and Cultural Centre – CCCM, I.P.) in Lisbon. The Museum of the Centre, which has a “twin institution” in Macau, houses an assortment of about 3,000 objects. These artefacts, distributed on two floors, are made of diverse materials and belong to different periods, which span from the Neolithic time to the twenty-first century. The building that hosts the Museum, the Research Centre and the Library was used by the Red Cross during World War I and became headquarter of the nation’s ex-servicemen’s organisation, the Portuguese Legion. After 1974, the building was used to house refugees from old Portuguese colonies. When the building was chosen to host the Macau Scientific and Cultural Centre, the renovation project was conceived by Paulo-Guilherme Tomáz Dúlio Ribeiro D’Eça Leal (1932 – 2010) (vide CCCM, I.P.).

A permanent exhibition is displayed on the two lower floors of the renovated four-storey building of the Centre. On the ground floor, visitors are welcomed by the bust of the tycoon Stanley Ho (何鴻燊; 1921 – 2020), on the left there is a tiny cafeteria, with a beautifully carved wooden panel probably of the Qing dynasty. The first part of the permanent exhibition is constituted by maps, books and artefacts made of various materials (terracotta, porcelain, wood, bronze and textiles) and is organised in order to provide a reconstruction of the history of Macau from the 16th century up to the handover, which occurred on 20 December 1999. On the same floor, a unique scale model of a “Black Ship” (“Nau do Trato” or kurofune 黑船), gives to the visitors the opportunity to immerse themselves into an imaginary journey along the maritime trade routes during the age of exploration, which are also displayed in interactive maps. Two guardian lions at the bottom of beautiful wooden stairs give access to the first floor where one has the chance to admire five thousand years of Chinese art. Highlights of the collection are the Museum’s shiwan ware (石灣窯), one of six known “Jorge Alvrz [Álvares] bottles” made of porcelain with underglaze blue, oil paintings on Macau landscapes and “Thomas Pereira”, gouache on paper by the contemporary artist and collector José de Guimarães (cf. CCCM, I.P.).

The majority of the artefacts displayed in the permanent exhibition comes from António Sapage’s collection. António Manuel dos Santos Sapage was born in Macau on January 26, 1949. From a very young age, he had demonstrated a specific interest in studying and collecting Chinese art. He had soon accumulated a long experience in Asian art and turned Macau in one of the world’s main centres for the exchange of artworks from Asia. His activities were well known in New York, London, Amsterdam, Monaco, Hong Kong, P. R. China and Portugal. He was nominated vice-chairman of the Association of the Collectors of Macau (Associação dos Coleccionadores de Macau), honorary and permanent director of the Association of Experts and Collectors of Chinese Antiquities of the Guangdong Province (Peritos e Coleccionadores de Antiguidades Chinesas da Província de Guangdong), and he became member of the Hong Kong Museum Society and of London’s Oriental Ceramic Society. For this reason and for his commitment to the promotion of the collection, study and knowledge of Chinese art in Macau, as well as for his role in triggering the internationalisation of Macau as privileged art market for collectors of Asian art, on 27 September 1999, he was awarded with the medal of Cultural Merit by Governor Vasco Rocha Viera (art. 7º, Decreto Lei nº 42/82/M, cf. Boletim).

Funerary procession. Cortejo funerário.

©Macau Scientific and Cultural Centre, I.P.

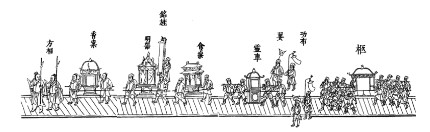

On the ground floor of the Museum, at the entrance, lies the funerary procession protected by a glass box. This incomplete set is of unknown authorship and it is estimated to have been manufactured in China during the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644 CE) (CCCM, I.P.). At first glance, even an inexpert eye notices that some pieces as well as some accessories are missing (i.e. banners, musical instruments, horses, among others). This aspect is confirmed by the beautiful iconographical reconstruction of a funerary procession depicted in the “Master Zhu’s family rituals” Jiali yijie 家禮儀節 (1608) attributed to Qiu Jun 邱濬 (1421–1495 CE) (apud Zhu; Ebrey, 1991: 118-119). This iconography can suggest, although cannot be understood as a fixed pattern, the distribution of the burial figurines (mingqi 明器) extant in the procession. Mingqi, which literally means “bright goods,” were popularised during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) and continued to be produced over time, providing not only details on the worldly life, but also insights into afterlife (Colla, 2012: 181). Together with other funerary structures (i.e. spirit-road sculptures pathways), they aimed at performing the deceased social role, beside ensuring the well-being of the dead, which was pivotal for the harmonious living of all those the dead left behind.

Depois de Funeral Procession in Jiali yijie 家禮儀節 vol. 5 juan 卷 54a-b (apud Zhu; Ebrey, 1991: 118-119). Adaptada pelo autor.

A funeral was perceived as a religious and social event that mediates between the individual, the family, and the community, imbued with diverse socio-political elements. Since the implementation of the complex system of Zhou death rituals, which were simplified by Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200 CE) in his Family Rituals (Zhu; Ebrey, 1991) in the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE) and further reformed in the following dynasties, one witnesses the bureaucratisation of the afterworld.

Because the sphere of ancestral influence was considered closer to the lives of their immediate descendants, funerary ritual practices followed the extant social hierarchy and they were considered a powerful means for constructing and consolidating social relations among the living. The funeral was seen as an opportunity to reaffirm social status and networks, but also to prevent possible injuries caused by evil spirits through offerings to deities and ancestral spirits.

Therefore certain rituals were performed and protective spells pronounced, written down, and buried in the tomb, which starting from the first century had become the lieu of ritual offerings for the deceased, substituting the previous temples. Long processions escorted the coffin to the burial ground and the ceremony of interment passing through a the “spirit pathway” (shendao 神道) flanked by huge and large stone statues, which antecedes the burial ground. These kind of artefacts show the need to materialize a system of mutual dependence between the living and the dead, which is also common in other East Asian systems.

Funerary processions, as those depicted in the Jiali yijie (Qiu; Yang; Zhu, 1608; Zhu; Ebrey, 1991: 118-119), are just a fragmentary picture of the whole scenario. This includes: Exorcists (fangxiang 方相), Incense Altar (xiang’an 香案), Grave Goods (mingqi 明器), Funerary Streamer bearing the title of the deceased (mingjing 銘旌), Food Table (shi’an 食案) and finally the Soul Carriage (lingche 靈車) precede the coffin (jiu 柩) accompanied by Shades Streamers (sha 翣 and gongbu 功布). These objects did not only depict the funerary procession per se, but were also believed to possess innate powers that ‘made clear’ the separation between the dead and the living as suggested by Xunzi (ca. 310–215 BC) (Lagerwey; Kalinowski, 2009: 9) and the way to express the sorrowful feelings (ai 哀) of the mourner (Cook, 1997: 18). In the fourth and longest chapter of Zhu Xi’s Family Rituals we can read: “[w]hen the coffin travels, the male and female mourners, from the presiding ones on down, walk behind it, wailing. The seniors come after the other mourners, followed by relatives without mourning obligations, then guests. Relatives and friends set up a tent beyond the city wall on the side of the road as a resting place for the coffin; they make an oblation there. On the road, the mourners wail whenever grief is felt” (Zhu, Ebrey 1991: 67).

However, this was neither a fixed distribution of performers, nor the model applied to each funeral. Historical implementations, religious believes and other elements affected these rituals, which were also influenced by local customs and historical times. Therefore, these mingqi depicting funerary processions of the Ming dynasty represent a preoccupation to fix any minute detail of ritual action based on social hierarchy in order to show the status of the deceased person, to show filial piety (xiao 孝), as well as to keep harmony between the living world and the afterlife sphere. In sum, they are a simulacrum with a powerful cathartic dimension (Colla, 2012: 181) aimed at mediating mourning and grief.

Acknowledgements: Carmen Amado Mendes (President of the CCCM, I.P.) and Rui Abreu Dantas (Coordinator of the Division of Museology, CCCM, I.P.)

Bibliography and useful links:

“António Sapage”, Museum of the CCCM, I.P. [18 January 2023] https://www.cccm.gov.pt/en/museum/antonio-sapage/.

Barreto, Luís Filipe; Maria Manuela d’Oliveira Martins and Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau. 1999. Guia Do Museu Centro Científico E Cultural De Macau. Macau: Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologia.

Barreto, Luís Filipe Alexandra and Costa Gomes “Criação do Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau – CCCM – Uma breve apresentação.” Suplemento – Revista Oriente Ocidente Ns. 33 e 34 II Série (2016-2017), pp. 1-11, [18 January 2023] https://issuu.com/iimacau.

Boletim Oficial de Macau – I SÉRIE – nº 39-27-9-1999, [18 January 2023] https://images.io.gov.mo/bo/i/99/39/pt-350-99.pdf

CCCM, I.P. – Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau, site: https://www.cccm.gov.pt/en/

Clunas, Craig. 2007. Empire of Great Brightness: Visual and Material Culture of Ming China, 1368–1644. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Colla, Elisabetta. 2012, ““Animism, Magic and the Omnipotence of Thought”: Ritualistic Artefacts and Mourning Mediation in Imperial China”. Panic and Mourning: The Cultural Work of Trauma, edited by Daniela Agostinho, Elisa Antz and Cátia Ferreira, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 181-192. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110283143.181.

Cook Scott. 1997. “Xun Zi on Ritual and Music.” Monumenta Serica 45 (1997) S. [1] pp. 1 – 38.

Ebrey, Patricia Buckley. 1991. Confucianism and Family Rituals in Imperial China: A Social History of Writing about Rites. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lagerwey John and Marc Kalinowski, eds. 2009. Early Chinese Religion Part One: Shang through Han (1250 Bc-220 Ad). Leiden: BRILL.

Rawski, Evelyn Sakakida and James L Watson. 1988. Death Ritual in Late Imperial and Modern China (Studies on China; 8). University of California Press.

Sapage, António Manuel dos Santos; Maria Alexandra da Costa Gomes and Palácio de Queluz (Museum : Queluz Portugal). 1994.Do Neolítico Ao Último Imperador: A Perspectiva De Um Coleccionador De Macau. Macau Lisboa: Governo de Macau; Instituto Português do Património Arquitectónico e Arqueológico.

Sapage, António. 1992. Porcelana Chinesa De Exportaçaõ : Diálogo Entre Dois Mundos = Zhongguo Wai Xiao Ci : Zhong Xi Hui Cui. Macau: Galeria de Leal Senado.

Sapage, António; José Carlos Morais; Weichi Zhang: Museu Luís de Camões. 1995. Shiwan Selecção De Obras Da Colecção Do Museu Luís De Camões; a Selection of Works from the Colection Collection of the Luís De Camões Museum; 27 De Setembro De 1995 = Shiwan-Cuizhen. (Location: Press – no data available).

Sapage, António. 1989. “Porcelana No Comércio Luso-Chinês.” Oceanos N. 14 (jun. 1993) pp. 31-38.

Qiu Jun 丘濬; Yang Tingyun 楊廷筠 and Zhu Xi 朱熹. 1997. Rituals of Wen gong’s [Zhu Xi] Family Rituals [Wengong jiali yijie 文公家禮儀節] (1608). Jinan: Qilu shushe chubanshe.

Zhu Xi and Patricia Buckley Ebrey. 1991. Chu Hsi’s Family Rituals: A Twelfth-Century Chinese Manual for the Performance of Cappings, Weddings, Funerals, and Ancestral Rites. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Estas figuras tumulares de cerâmica policromada, que pertence à coleção permanente do Museu do Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau em Lisboa, representam um conjunto de uma procissão funerária em miniatura. O Museu do Centro, que tem uma “instituição gémea” em Macau, conserva um acervo de cerca de 3.500 objetos. Estes artefactos feitos de diversos materiais estão distribuídos por dois pisos e pertencem a diferentes períodos, que vão desde o Neolítico até ao século XXI. O edifício onde se encontram instalados o Museu, o Centro de Investigação e a Biblioteca era a antiga sede da Cruz Vermelha Portuguesa. Quando o edifício foi escolhido para acolher o Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau, foi realizado um projeto de reabilitação que esteve a cargo de Paulo-Guilherme Tomáz Dúlio Ribeiro D’Eça Leal (1932 – 2010) (vide CCCM, I.P.).

O edifício de quatro andares do Centro acolhe nos dois andares inferiores uma exposição permanente. No rés-do-chão, os visitantes deparam-se com o busto de Stanley Ho (何鴻燊; 1921 – 2020) e, entrando, encontram à esquerda uma pequena cafetaria com um belo painel de madeira entalhada provavelmente da dinastia Qing. Sempre no rés-do-chão, o acervo da exposição permanente é caracterizado por mapas, livros e artefactos feitos de diversos materiais (terracota, porcelana, madeira, bronze e têxteis), que estão organizados de forma a proporcionar uma reconstituição da história de Macau desde o século XVI até a transferência da soberania, que ocorreu no dia 20 de Dezembro de 1999. No mesmo piso, uma reprodução em escala da “Nau do Trato” (“Navio Negro” ou kurofune 黑船) proporciona aos visitantes uma oportunidade única de mergulharem numa viagem imaginária ao longo das rotas comerciais marítimas da época das explorações, que são também exibidas em mapas interativos. Ao pé de belas escadas de madeira que dão acesso ao primeiro piso, no qual se pode admirar cinco mil anos de arte chinesa, encontram-se dois leões guardiões. Da coleção do Museu destacam-se as cerâmicas shiwan (石灣窯), uma das seis conhecidas “garrafas Jorge Alvrz [Álvares]” em porcelana branca decorada a azul-cobalto sob o vidrado, as pinturas a óleo com paisagens de Macau, e “Thomas Pereira”, um guache sobre papel do artista contemporâneo e colecionador José de Guimarães (cf. CCCM, I.P.)

A maioria dos objetos da exposição permanente provem da coleção de António Sapage. António Manuel dos Santos Sapage nasceu em Macau a 26 de Janeiro de 1949. Desde muito jovem demonstrou um interesse específico em estudar e colecionar arte chinesa. Em pouco tempo acumulou uma grande experiência na arte asiática e transformou Macau num dos principais centros mundiais de intercâmbio de obras de arte asiáticas. As suas atividades eram bem conhecidas em Nova Iorque, Londres, Amsterdão, no Mónaco, em Hong Kong, na R. P. da China e em Portugal. Chegou a ser nomeado vice-presidente da Associação dos Colecionadores de Macau e diretor honorário e permanente da Associação dos Peritos e Colecionadores de Antiguidades Chinesas da Província de Guangdong, e tornou-se membro da Hong Kong Museum Society e da Oriental Ceramic Society de Londres. Por este motivo e pelo seu empenho na promoção da coleção, estudo e conhecimento da arte chinesa em Macau, bem como pelo seu papel no desencadeamento da internacionalização de Macau como mercado privilegiado de arte para colecionadores de arte asiática, no dia 27 de Setembro de 1999, foi agraciado com a medalha de Mérito Cultural pelo Governador Vasco Rocha Vieira (art. 7º, Decreto Lei nº 42/82/M, cf. Boletim).

À entrada do Museu, no rés-do-chão, encontra-se o cortejo fúnebre protegido por uma vitrine. Este conjunto de figurinhas, de autoria desconhecida, encontra-se incompleto e estima-se que tenha sido fabricado na China durante a dinastia Ming (1368 – 1644 dC) (CCCM, I.P.). À primeira vista, até um olhar inexperiente nota que faltam algumas peças, bem como alguns acessórios (como por exemplo, estandartes, instrumentos musicais, cavalos, entre outros). Trata-se de um aspeto que poderá ser confirmado comparando com a reconstrução iconográfica de uma procissão funerária retratada nos “Rituais Familiares do Mestre Zhu” – Jiali yijie 家禮儀節 (1608) atribuído à Qiu Jun 邱濬 (1421–1495 EC) (apud Zhu; Ebrey, 1991: 118-119). Esta iconografia, embora não possa ser entendida como um padrão fixo, pode sugerir como eram distribuídas as estatuetas funerárias (mingqi 明器) do cortejo. Os mingqi, cujo termo significa literalmente “bens brilhantes”, tornaram-se populares durante a dinastia Han (206 a.C.-220 d.C.) e continuaram a ser produzidos ao longo do tempo, fornecendo não apenas detalhes sobre a vida mundana, mas também uma compreensão sobre a vida após a morte (Colla, 2012: 181). Juntamente com outros elementos funerários (i.e. as esculturas do dito caminho dos espíritos), os mingqi eram representativos do papel social do defunto, para além de assegurarem o bem-estar dos mortos, que era fundamental para a harmonia de todos os que o defunto havia deixado para trás.

O funeral era encarado como um evento religioso e social, isto é, uma mediação entre o indivíduo, a família e a comunidade, e por isso acabava por ser imbuído de diversos elementos sociopolíticos. O complexo sistema de rituais funerários, implementado durante a dinastia Zhou (1046 AEC – 256 AEC) foi simplificado durante a dinastia Song (960–1279 EC) por Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200 EC) nos seus “Rituais Familiares” (Zhu; Ebrey, 1991). Estes rituais, que foram posteriormente reformados nas dinastias seguintes, representam a burocratização do além.

A esfera de influência ancestral chegava à vida dos seus descendentes mais próximos e as práticas funerárias seguiam a mesma hierarquia social em vigor, pelo que os rituais eram também considerados um meio poderoso para construir e consolidar os laços sociais entre os vivos. O funeral era visto como uma oportunidade para reafirmar a posição de um individuo na sociedade e para consolidar a sua rede de influências, sendo ainda que as oferendas às divindades e espíritos ancestrais eram vistas como uma forma de prevenir possíveis interferências causadas pelos espíritos malignos.

A seguir, eram praticados certos rituais e proclamados feitiços de proteção que, quando escritos, eram enterrados no túmulo, o qual, a partir do século primeiro, se tornaria local de oferendas para os mortos, substituindo-se aos templos correspondentes. As longas procissões que escoltavam o caixão até o cemitério, antes da cerimónia do enterro, passavam por um “caminho espiritual” (shendao 神道) ladeado por enormes e grandes estátuas de pedra. Este tipo de artefactos testemunha a necessidade de materializar a relação de dependência que existia entre vivos e mortos, algo comum a outros sistemas religiosos da Ásia Oriental.

As procissões funerárias, tais como as representadas no Jiali yijie (Qiu; Yang; Zhu, 1608; Zhu; Ebrey, 1991: 118-119), são apenas uma imagem fragmentária de um todo, que inclui exorcistas (fangxiang 方相), um altar para o incenso (xiang’an 香案), artefactos tumulares (mingqi 明器), um estandarte funerário vertical com o título póstumo do falecido (mingjing 銘旌), uma mesa para as oferendas alimentares (shi’an 食案) e, finalmente, uma carruagem da alma (lingche 靈車) que precede o caixão (jiu 柩) acompanhada por leques rituais e fitas (sha 翣 e gongbu 功布). Esses acessórios não eram apenas parte da procissão funerária per se, mas acreditava-se que possuíssem poderes sobrenaturais inatos capazes de manter separados os mundos dos vivos e dos mortos, como indicado por Xunzi (ca. 310–215 aC) (Lagerwey; Kalinowski, 2009: 9) e uma forma para expressar os sentimentos de tristeza (ai 哀) dos enlutados (Cook, 1997: 18). No quarto e mais longo capítulo dos Rituais Familiares de Zhu Xi, podemos ler: “[quando] o caixão é transportado, mulheres e homens enlutados marcham atrás deles num lamento, aos que presidem, seguem todos os outros. Os mais velhos precedem os outros enlutados, seguidos pelos parentes sem obrigações de luto e finalmente pelos convidados. Para abrigar o caixão, os parentes e amigos instalam uma tenda fora das muralhas citadinas, à beira da estrada, onde fazem uma oblação. Ao longo de todo o caminho, o cortejo continua em lamento do seu pesar” (Zhu, Ebrey 1991: 67)

No entanto, esta distribuição de figurinhas não é fixa, nem poderá ser entendida como modelo para todos os funerais. As práticas históricas, as crenças religiosas e outros elementos influíram sobre estas procissões, que foram também influenciados por costumes locais e momentos históricos. Portanto, esses mingqi que representam procissões funerárias da dinastia Ming representam uma preocupação em fixar qualquer detalhe minucioso da ação ritual baseada na hierarquia social, a fim de mostrar o estatuto da pessoa falecida, evidenciar a piedade filial (xiao 孝), e ainda manter a harmonia entre o mundo dos vivos e a esfera da vida após a morte. Em suma, são um simulacro com uma poderosa dimensão catártica (Colla, 2012: 181) destinado a mediar o luto e o pesar.

Agradecimentos: Carmen Amado Mendes (Presidente do CCCM, I.P.) e Rui Abreu Dantas (Coordenador da Divisão de Museologia, CCCM, I.P.)

Chinese Pigeon Whistles from the Slovene Ethnographic Museum

by Dr. Klara Hrvatin, Department of Asian Studies, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia

Image copyright © Slovene Ethnographic Museum

Museum: The Slovene Ethnographic Museum (photo Blaž Verbič)

Inventory No.: Figure 1: 244 MG, Figure 2: 243 MG, Figure 3: 239 MG, Figure 4: 245 MG, Figure 5: 242 MG, Figure 6: 236 MG (Figures are labelled from left to right, from top to bottom.)

Name: Pigeon whistles

Author: Unknown

Place of Execution: China

Dating: 19th century

Material: gourd, bamboo, ivory

Dimensions (cm): height: 4-6; width: 4-5; length: 4-6 cm

The pigeon whistle, known in China as geling 鴿鈴 or geshao 鴿哨, is a small musical instrument belonging to the group of so-called Aeolian musical instruments. The whistle is attached to the tail of the pigeon so that it produces a sound when it flies. The flute is made of light materials such as gourd and bamboo and varnished. The makers enrich their image with engraved patterns and ivory ornaments. In China, the pigeon whistle has been used at least since the beginning of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), but it is also common in other Asian regions, such as Indonesia and Japan. In the past, the sound of the pigeon whistles, also known as “heavenly music”, presented a distinctive sound of Beijing.

The Slovene Ethnographic Museum holds a collection of 14 pigeon whistles. They are part of a larger collection of intendant Ivan Skušek Jr. (1877–1947), comprised of various objects such as paintings, statues, porcelain vessels, clothes, shoes, musical instruments, games, books, albums, photographs, coins, garden ceramics, furniture, and much more. As a special feature of the collection, Chinese instruments can be labelled as a rare and most extensive collection in Slovenia, including pigeon whistles.

The examples shown above present the three most common types of pigeon whistles found in the collection; the gourd type (Figure 3, 5, and 6), the tubular type (Figure 2) and the combined type (Figure 1 and 4). Among all these types, the gourd type is the most common representative – a type of pigeon whistle that has a carved gourd as its base to which bamboo sub-whistles are attached. The largest number of them is represented by small-sized pigeon whistles, with three sub-whistles and flower patterns in black on red or yellow (Figure 6).

Also more numerous are specimens of a combined type of pigeon whistles – the type with a gourd body in the middle, also called “star belly”, with a narrow tube attached to the front and a larger and wider tube attached to the back. In the photos you can see the representative of the “seven-star whistle” (Figure 4) and the “eleven-eye whistle” (Figure 1), which are similar in appearance. The former has a green lacquered gourd while the latter a dark red gourd; all other parts are unlacquered. In contrast to the abundance of gourd and combined type of pigeon whistles in the Skušek collection, there is only one example of the tubular type (Figure 2), which is characterised by clean lines, an overall construction of bamboo in natural colour, and a pure tone, with the shorter tube tuned higher than the longer tube.

Each type of pigeon whistle has its own distinctive sound. In a common arrangement, the gourd type of pigeon whistle would represent a bass tone, the tubular type would represent a soprano (a shorter pipe) and an alto (a longer pipe), while the combined type can produce tones of different pitch simply by virtue of its structure. The pigeon whistle is also distinguished by its special character – a carved Chinese character engraved on the back of the whistle. Although most of the pigeon whistles from the Skušek collection have engraved characters, they cannot be attributed to the major makers, i.e. the eight famous pigeon whistle makers.

Bibliography and useful links:

Hrvatin, Klara. Golobje piščali iz Skuškove zbirke Slovenskega etnografskega muzeja (Pigeon whistles from the Skušek collection of the Slovene Ethnographic Museum). Bulletin of the Slovene Ethnological Society 60, no. 1 (2020): 42-55.

Golobje piščali v Skuškovi zbirki (Pigeon Whistles in the Skušek Collection). VAZ; https://vazcollections.si/golobje-piscali-v-skuskovi-zbirki/, 22.1.2023.

Wang, Shixiang. Beijing Pigeon Whistles. Peking: Liaoning Education Press, 1999.

Wang, Shixiang. Tradition and Innovation: On Pigeon Whistles. In: Iftikhar Dadi (ur.), The Future is Handmade: The Survival and Innovation of Crafts. Prince Claus Fund Journal 10a (special issue), 2003, 14–30.

Hoose, Harned Pettus. Peking Pigeons and Pigeon-flutes. Peking: College of Chinese Studies, California College in China, 1938.

Laufer, Berthold. Chinese Pigeon Whistles. Scientific American 98/22, 1908, 394; https://www.jstor.org/ stable/10.2307/26018442, 4. 1. 2020.

China Today, The Pigeon Whistle: A Defining Sound of Old Beijing (documentary film), 27. 11. 2019; https://www.facebook.com/chinatoday1952/videos/2377966232444442, 23. 1. 2023.

The Beijing Pigeon Whistle – and Pigeon training tips / More China, 1.2.2018; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3i5xtadHPRA&ab_channel= =更中国MoreChina, 22.1.2023.

Trending China, Colin Siyuan Chinnery. Recording New and Old Sounds of Beijing, 2. 3. 2019; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V5EB73v1k9M&ab_channel=2MMediaGroup, 22. 1. 2023.

Muzej: Slovenski etnografski muzej (foto Blaž Verbič)

Inventarna št.: Slika 1: 244 MG, Slika 2: 243 MG, Slika 3: 239 MG, Slika 4: 245 MG, Slika 5: 242 MG, Slika 6: 236 MG (Slike so označene od leve proti desni, od zgoraj navzdol)

Ime: Golobje piščali

Avtor: Neznan

Kraj: Kitajska

Datacija: 19. stoletje

Material: buča, bambus, slonovina

Mere (v cm): višina: 4-6; širina: 4-5; dolžina: 4-6

Golobja piščal, na Kitajskem znana kot geling 鴿鈴 ali geshao 鴿哨, je majhno glasbilo, ki spada v skupino tako imenovanih eolskih glasbenih instrumentov. Piščalka je pritrjena na rep goloba, tako da oddaja zvok, ko golob leti. Izdelana je iz lahkih materialov, kot sta buča in bambus, ter lakirana. Izdelovalci njeno podobo večkrat obogatijo z graviranimi vzorci in okrasi iz slonovine. Na Kitajskem se golobja piščal uporablja vsaj od začetka dinastije Qing (1644–1912), vendar je pogosta tudi v drugih azijskih območjih, kot sta Indonezija in Japonska. V preteklosti je bil zvok golobjih piščali, znan tudi kot »nebeška glasba«, prepoznaven zvok Pekinga.

Slovenski etnografski muzej hrani zbirko 14 golobjih piščali. So del večje zbirke intendanta Ivana Skuška ml. (1877–1947), ki jo sestavljajo različni predmeti, kot so slike, kipi, porcelan, oblačila, glasbila, igre, knjige, albumi, fotografije, kovanci, vrtne keramične garniture, pohištvo itn. Kot posebnost zbirke lahko kot redko in najobsežnejšo zbirko na slovenskih tleh označimo tudi kitajska glasbila, vključno z golobjimi piščali.

Zgoraj prikazani primeri predstavljajo tri najpogostejše vrste golobjih piščali, ki jih najdemo v zbirki: bučni tip (Slike 3, 5 in 6), cevni tip (Slika 2) in kombinirani tip (Sliki 1 in 4). Najpogostejši predstavnik je bučni tip – vrsta golobje piščali, ki ima za osnovo izrezljano bučo, na katero so pritrjene bambusove pomožne piščali ali podpiščali. Najštevilčnejši so primerki bučnega tipa golobjih piščali manjšega formata s tremi podpiščalmi in cvetličnimi vzorci v črni barvi na rdeči ali rumeni podlagi (Slika 6).

Številčnejši so tudi primerki kombiniranega tipa golobjih piščali – tip z bučnim telesom v sredini, imenovan tudi zvezdni trebuh, z od spredaj pritrjeno ozko cevjo, zadaj pa z večjo in s širšo cevjo. Na fotografijah lahko vidimo predstavnika golobje piščalisedmih zvezd (Slika 4) in golobje piščalienajstih oči(Slika 1), ki sta si na videz podobna. Prvi ima zeleno lakirano bučo, drugi pa temno rdečo bučo; vsi ostali deli so nelakirani. V nasprotju s številčnostjo piščali bučnega in kombiniranega tipa je v Skuškovi zbirki le en primer cevnega tipa, t.i. dvocevni tip, ki ga odlikujejo čiste linije in celotna izdelava iz bambusa v naravni barvi.

Vsak tip golobje piščali ima svoj značilni zvok. Če si jih zamislimo v skupni postavitvi, bi predstavljal bučni tip golobjih piščali basovski ton, cevni tip sopranski (krajša cev) in altovski (daljša cev), kombinirani tip pa že sam po sebi vsebuje vse omenjene tone. Golobje piščali odlikuje tudi posebna oznaka – vgravirana kitajska pismenka na zadnji strani piščali. Čeprav so na večini golobjih piščali iz Skuškove zbirke vrezane oznake, ki bi lahko služile kot logotip izdelovalcev, pa teh ne moremo uvrstiti med osem glavnih izdelovalcev golobjih piščali.

Bibliografija

Hrvatin, Klara. Golobje piščali iz Skuškove zbirke Slovenskega etnografskega muzeja. Glasnik Slovenskega etnološkega društva 60, št. 1 (2020): 42-55.

Golobje piščali v Skuškovi zbirki. VAZ; https://vazcollections.si/golobje-piscali-v-skuskovi-zbirki/, 22.1.2023.

Wang, Shixiang. Beijing Pigeon Whistles. Peking: Liaoning Education Press, 1999.

Wang, Shixiang. Tradition and Innovation: On Pigeon Whistles. V: Iftikhar Dadi (ur.), The Future is Handmade: The Survival and Innovation of Crafts. Prince Claus Fund Journal 10a (special issue), 2003, 14–30.

Hoose, Harned Pettus. Peking Pigeons and Pigeon-flutes. Peking: College of Chinese Studies, California College in China, 1938.

Laufer, Berthold. Chinese Pigeon Whistles. Scientific American 98/22, 1908, 394; https://www.jstor.org/ stable/10.2307/26018442, 4. 1. 2020.

China Today, The Pigeon Whistle: A Defining Sound of Old Beijing (dokumentarni film), 27. 11. 2019; https://www.facebook.com/chinatoday1952/videos/2377966232444442, 23. 1. 2023.

The Beijing Pigeon Whistle – and Pigeon training tips / More China, 1.2.2018; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3i5xtadHPRA&ab_channel= =更中国MoreChina, 22.1.2023.

Trending China, Colin Siyuan Chinnery. Recording New and Old Sounds of Beijing, 2. 3. 2019; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V5EB73v1k9M&ab_channel=2MMediaGroup, 22. 1. 2023.

Rabab Pasisir in the Collection of the Asia and Pacific Museum in Warsaw

By Maria Szymańska-Ilnata

Museum: The Andrzej Wawrzyniak Asia and Pacific Museum in Warsaw

Inventory No.: MAP 20804

Name: Rabab pasisir lute

Author: Dalimus Arip (1951-)

Place of Execution: Indonesia, West Sumatra, Swahlunto

Dating: c. 1985

Material: wood, coconut, metal, string, ant excrements, wire

Dimensions (cm): instrument: height: 64; width: 18; length: 10; bow: height: 64; width: 8; length: 1.5

Image copyright © The Asia and Pacific Museum

The rabab pasisir is part of the collection of musical instruments and is displayed at the permanent exhibition “The Sound Zone” at the Asia and Pacific Museum in Warsaw. It was made by Dalimus Arip in 1985 ca. and used by him until 2015 when it was bought by the curator of the musical instruments collection at the Asia and Pacific Museum during her field research conducted in West Sumatra. Rabab pasisir or biola comes from the region of Pesisir, but has spread to other regions of West Sumatra. The name “biola” refers to the shape of the instrument which resembles the European violin. It is very likely that the violin was brought to Sumatra by the Portuguese who were the first Europeans in that region, and was later adapted by local people to their traditional music. Confirmation of this view of the instrument’s history exists also in the Sumatran classification of instruments which situates rabab pasisir in the category called “asal Barat”, namely “coming from the West”1. It shows the Minangkabau people’s awareness of the origin of this instrument which is called now “traditional”. Rabab pasisir has the shape of a violin but differs in proportions and materials. Almost each rabab pasisir maker introduces his own special feature; for example, some of the instruments are very slim and others more rounded. Coconut is used to make the bridge while buffalo horn is used for the tailpiece. Rabab pasisir has four strings, although only three of them are used. As many musicians and rabab pasisir makers claim, the fourth string is necessary for the “balance”, and cannot be removed although is not necessary for playing.

1 Margaret J. Kartomi, On Concepts and Classifications of Musical Instruments (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990): 225.

Even though the rabab’s shape and construction is reminiscent of those of a European violin, its playing technique is completely different. The player sits with his legs crossed, holding the rabab in a vertical position, propping it against the floor or his foot. The rabab displayed sports a dark stain at the back of the sound box, which – according to the maker and owner of the instrument – marks the place where an opening for inserting the sound post used to be. The opening was filled with excrements of a special kind of forest ants. Inside the sound box there is a little piece of silver paper, folded into a cube (most probably a cigarette package of some sort), on which a magic spell is written, according to the musician.

The rabab is used to provide accompaniment for epical narratives called kaba (earlier tradition) and songs. It is played solo or together with a drum, most often the single-skin rabana, usually to accompany singing.

The Hornbostel-Sachs system of musical instruments classification:

3 CHORDOPHONES / 32 Composite chordophones / 321 Lutes / 321.3 Handle lutes / 321.31 Spike lutes / 321.312-7 Spike box lutes or spike guitars sounded by bowing

Dalimus Arip with his rabab pasisir, May, 9th 2015,

Sawahlunto, photo: M. Szymanska-Ilnata

Dalimus Arip ze swoim rababem pasisir, 9 maja 2015 r., Sawahlunto, fot. M. Szymańska-Ilnata

Bibliography:

Eny Christyawaty i Maryetti. Pemain rabab pasisia: dari pengabdian seni ke profesi. Studi kasus 5 orang rabab pasisia di Pesisir Selatan Sumatera Barat. Padang: Balai Kajian Sejarah dan Nilai Tradisional, 2005.

Erizal. Instrumen musik chordophone Minangkabau. Padang Panjang: Akademi Seni Karawitan Indonesia, 1995.

Hajizar i Muhammad Hidayat Rahz. Tradisi pertunjukan rabab Minangkabau. Bandung, Indonesia: Masyarakat Seni Pertunjukan Indonesia, 1998.

Hartitom. Rabab pasisia dalam lagu Sikambang aia aji ditinjau dari aspek musikologis: studi kusus di kecamatan Lengayang, kabupaten Pesisir Selatan. Padang: Istitut Keguruan dan Ilmu Pendidikan, 1998.

Kartomi, Margaret J. Musical Journeys in Sumatra. University of Illinois Press, 2012.

———. On Concepts and Classifications of Musical Instruments. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Muzeum: Muzeum Azji i Pacyfiku im. Andrzeja Wawrzyniaka w Warszawie

Numer inwentarza: MAP 20804

Nazwa: Lutnia rabab pasisir

Autor: Dalimus Arip (1951-)

Miejsca pozyskania: Indonezja, Zachodnia Sumatra, Sawahlunto

Datowanie: ok. 1985

Tworzywa: drewno, kokos, metal, sznurek, odchody mrówek, drut

Wymiary: instrument: wys. 64, szer. 18, gł. 10, smyczek: wys. 64, szer. 8, gł. 1,5

Rabab pasisir należy do kolekcji instrumentów muzycznych i jest prezentowany na stałej wystawie „Strefa dźwięków” w Muzeum Azji i Pacyfiku w Warszawie. Został wykonany przez Dalimusa Aripa ok. 1985 r. i był przez niego używany do 2015 r., kiedy zakupiła go do muzealnej kolekcji instrumentów muzycznych Muzeum Azji i Pacyfiku jej kuratorka podczas badań terenowych prowadzonych na Sumatrze Zachodniej. Rabab pasisir, zwany też biolą pochodzi z regionu Pesisir, ale jest popularny także w innych regionach Zachodniej Sumatry. Nazwa „biola” odnosi się do kształtu instrumentu, który przypomina europejskie skrzypce. Prawdopodobnie skrzypce zostały przywiezione na Sumatrę przez Portugalczyków, którzy dotarli tam jako pierwsi Europejczycy, a następnie zostały zaadaptowane przez lokalnych mieszkańców do ich tradycyjnej muzyki. Potwierdzeniem tej tezy jest także miejsce instrumentu w tradycyjnej klasyfikacji instrumentów muzycznych z Sumatry, zgodnie z którą rabab pasisir należy do kategorii „asal Barat”, czyli „pochodzących z Zachodu”1. Wskazuje to na świadomość ludzi Minangkabau dotyczącą pochodzenia instrumentu, który obecnie określany jest mianem tradycyjnego. Rabab pasisir ma kształt skrzypiec, ale różni się od nich proporcjami i materiałami, z jakich jest wykonany. Prawie każdy budowniczy rababów wprowadza własne modyfikacje, na przykład niektóre rababy są bardzo wąskie, a inne zaokrąglone. Łupina orzecha kokosowego jest używana do wytwarzania mostka, a róg bawoli strunnika. Rabab pasisir ma cztery struny, mimo, że używane są tylko trzy z nich. Jak deklaruje wielu muzyków i budowniczych rababów, czwarta struna jest niezbędna do zachowania „równowagi” i nie może zostać zdjęta, choć nie jest potrzebna do grania.

Pomimo tego, że kształt i konstrukcja rababów bardzo przypomina europejskie skrzypce, technika gry na nich jest zupełnie inna. Muzyk siedzi ze skrzyżowanymi nogami, trzyma instrument pionowo i opiera o podłogę lub swoją stopę. Prezentowany rabab ma na tylnej płycie rezonansowej ciemną plamę, która – zgodnie z deklaracją budowniczego i właściciela instrumentu – zasłania otwór, przez który włożona była dusza. Otwór ten zaklejony zostały odchodami specjalnego rodzaju leśnych mrówek. Wewnątrz pudła rezonansowego znajduje się także złożony w kostkę mały kawałek srebrnego papieru (prawdopodobnie pochodzący z opakowania po papierosach), na którym – według muzyka – zapisane jest magiczne zaklęcie.

Na rababie wykonuje się akompaniament do epickich pieśni zwanych kaba (starsza tradycja) oraz piosenek. Akompaniując do śpiewu gra się na nim solo lub z towarzyszeniem bębna, najczęściej jednomembranowego, zwanego rabana.

W klasyfikacji Sachsa- Hornbostela:

3 CHORDOFONY / 32 Chordofony złożone / 321 Lutnie / 321.3 Lutnie drzewcowe / 321.31 Lutnie z drzewcem przelotowym / 321.312-7 Skrzynkowe lutnie lub gitary z drzewcem przelotowym pobudzane smyczkowaniem

Bibliografia:

Eny Christyawaty i Maryetti. Pemain rabab pasisia: dari pengabdian seni ke profesi. Studi kasus 5 orang rabab pasisia di Pesisir Selatan Sumatera Barat. Padang: Balai Kajian Sejarah dan Nilai Tradisional, 2005.

Erizal. Instrumen musik chordophone Minangkabau. Padang Panjang: Akademi Seni Karawitan Indonesia, 1995.

Hajizar i Muhammad Hidayat Rahz. Tradisi pertunjukan rabab Minangkabau. Bandung, Indonesia: Masyarakat Seni Pertunjukan Indonesia, 1998.

Hartitom. Rabab pasisia dalam lagu Sikambang aia aji ditinjau dari aspek musikologis: studi kusus di kecamatan Lengayang, kabupaten Pesisir Selatan. Padang: Istitut Keguruan dan Ilmu Pendidikan, 1998.

Kartomi, Margaret J. Musical Journeys in Sumatra. University of Illinois Press, 2012.

———. On Concepts and Classifications of Musical Instruments. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

1 Margaret J. Kartomi, On Concepts and Classifications of Musical Instruments (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990): 225

A Special Piece: a Celadon Gourd-shaped Ewer in Hamburg

By Maria Sobotka

DE: Abb. 1 – Die kürbisförmige Kanne aus Seladon mit Lotosblütenmuster in kupferroter Unterglasurmalerei aus der Goryeo-Periode, ausgestellt im Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (links). Rechts ein chinesisches Stück mit einer ähnlichen Form aus dem Zhejiang/Yue-Ofen, datiert in die Nördliche Song-Dynastie, 10. Jahrhundert. Bild aufgenommen von der Autorin, 2020.

This gourd-shaped ewer stems from the Kingdom of Goryeo (918–1392). There are only three jugs of this type in the world. One is in the Leeum Samsung Museum of Art in Seoul, one in the Freer and Sackler Galleries in Washington, D.C. – National Museum of Asian Art, and one in the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (MK&G). What makes this piece outstanding is the fine underglaze painting in copper red. In the 13th century, the pigment cobalt was the first pigment that could be used to paint beautifully on porcelain, as many blue and white porcelains from China, Persia, and later Europe attest. What potters failed in for a long time, but the Koreans were among the first to succeed in, was underglaze painting with copper oxide. For the underglaze red painting, copper oxide is applied on the body before firing. It turns red afterwards. The difficulty in controlling the copper oxide pigment came with limited success and therefore resulted in a scarce use of this decor. This jug is special as it is one of the earliest and most delicate examples that we know of in this very technique. It is also extremely finely crafted: you can see that every vein of the leaves and even the small figurine on the edge of the ewer – a child holding a lotus flower – are extremely concise and elaborately rendered as is the beautifully shaped body of the jug with its sleek spout and handle.

Justus Brinckmann (1843–1915) acquired this ewer from the Japanese art dealer Seisuke Ikeda (1839–1900) in Kyoto sometime before 1910. It underwent tremendous conservation treatment as you can see when you compare the current image with this historic photograph. The celadon ewer, located on the upper right, had been part of a display case during Brinckmann’s times as director. The jug in the Freer and Sackler Galleries was formerly owned by the collector Charles Lang Freer, who made a trip to Europe in the early 20th century and visited the MK&G in Hamburg. Perhaps he was inspired by Brinckmann’s purchase and somehow acquired a similar piece in the US?

DE: Abb. 2 – Die Seladon-Kanne im ursprünglichen Zustand, wie Justus Brinckmann sie erwarb und bevor sie im Leeum Samsung Museum of Art in Seoul restauriert worden ist. Archivmaterial. Copyright: Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg.

References:

See Valenstein, Meech-Pekarik, and Jenkins, 1980 Oriental Ceramics, the World’s Greatest Collections: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Ohio State University: p. 179 for a description of this technique.

Other information stems from research that has been conducted between 2018 and 2020 in the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg by the author as part of the re-organization of the Korean gallery.

For further information:

The ewer is published in the Korean Collection at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg. Catalogue of Overseas Korean Cultural Heritage. No. 35. National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage (ed.), 2017, Samsung Moonhwa Printing Co. Ltd., p. 29-31.

See Nora von Achenbach, Die Botschaft der Dinge. Eine koreanische Seladonkanne mit kupferroter Bemalung im Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, in Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, Neue Serie; Nr. 35 – Frühjahr 2018, p. 9-14 for more information on the restoration process.

Diese kürbisförmige Kanne stammt aus der Goryeo-Periode (918-1392). Weltweit gibt es nur drei Kannen dieser Art. Eine befindet sich im Leeum Samsung Museum of Art in Seoul, eine in den Freer and Sackler Galleries in Washington, D.C. – National Museum of Asian Art, und eine im Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (MK&G). Das Besondere an diesen drei Objekten ist die feine Unterglasurmalerei in Kupferrot. Das Pigment Kobalt war im 13. Jahrhundert das erste Pigment, mit dem die Malerei auf Porzellan in ästhetisch ansprechender Weise ausgeführt werden konnte, wie viele blau-weiße Porzellane aus China, Persien und später Europa bezeugen. Was vielen Töpfern lange Zeit misslang, und wo koreanische Töpfer früh die ersten Erfolge verbuchen konnten, war die Unterglasurmalerei mit Kupferoxid. Bei der roten Unterglasurmalerei wird Kupferoxid vor dem Brennen auf den Scherben aufgetragen. Während des Brandes „färbt“ es sich rot. Die Schwierigkeit besteht darin, das Kupferoxidpigment im Brand zu kontrollieren. Der mäßige Erfolg vieler Töpfer führte darum zu einer seltenen Verwendung dieses Dekors. Diese Kanne ist besonders, denn sie ist eines der frühesten und feinsten Beispiele, die wir kennen, die in dieser Technik gearbeitet ist. Der Dekor ist äußerst fein gearbeitet: Man sieht nicht nur jede Blattader auf den sich nach oben verjüngenden Blättern des Lotos, sondern auch die kleine Figur am Rand der Kanne – ein Kind oder Mönch mit Lotosblume in den Händen haltend – ist überaus präzise und kunstvoll gearbeitet, ebenso wie der elegant geformte Körper der Kanne mit seiner schlanken Tülle und dem geschwungenen Henkel.

Justus Brinckmann (1843-1915) erwarb diese Kanne vor dem Jahre 1910 von dem japanischen Kunsthändler Seisuke Ikeda (1839-1900) in Kyoto. Sie wurde umfassend restauriert, wie man unschwer erkennen kann bei vergleichender Betrachtung des aktuellen Bildes mit der historischen Fotografie (Abb. 2). Die Seladon-Kanne ist hier oben rechts zu sehen in einer Vitrine, die vermutlich Justus Brinckmann selbst als Direktor des Museums einrichtete. Der Krug in den Freer and Sackler Galleries war früher im Besitz des Sammlers Charles Lang Freer, der Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts eine Europareise unternahm und das MK&G in Hamburg besuchte. Vielleicht ließ er sich von Brinckmanns Kauf inspirieren und erwarb in den USA ein ähnliches Stück?

Nachweise:

Siehe Valenstein, Meech-Pekarik und Jenkins, 1980 Oriental Ceramics, the World’s Greatest Collections: Das Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Ohio State University: S. 179 für eine Beschreibung dieser Technik.

Weitere Informationen stammen aus Recherchen, die die Autorin zwischen 2018 und 2020 im Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg im Rahmen der Neuinstallation der koreanischen Galerie durchgeführt hat.

Für weitere Informationen:

Die Kannen sind im Katalog zur Korea-Sammlung des MK&G publiziert, Korean Collection at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg. Catalogue of Overseas Korean Cultural Heritage. No. 35. National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage (Hrsg.), 2017, Samsung Moonhwa Printing Co. Ltd., S. 29-31.

Siehe Nora von Achenbach, Die Botschaft der Dinge. Eine koreanische Seladonkanne mit kupferroter Bemalung im Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, in Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, Neue Serie; Nr. 35 – Frühjahr 2018, S. 9-14 für weitere Informationen über den Restaurierungsprozess.

Francisco Capelo, Portuguese Collector

By Mariana Araújo

Francisco Capelo studied economics and management at Lisbon Catholic University, graduating in 1977 and subsequently working as an investment banker and stockbroker until 1992. Later he served as chairman and executive board member and was a private equity investor in several companies (1993-2001).

As an art collector his interests are broad and mostly focused on building collections to be publicly viewed in museums and then ultimately publicly-owned. In the late 80’s and 90’s Capelo collected modern and contemporary Western art and later design and fashion. After a long trip to Asia in 1999 and subsequently, over the last 20 years, he has assembled a collection of over 1,300 works of art from that continent, driven by his fascination with the historical links between Asia and Portugal.

EN: Japan, Ogata Kenzan, early 18th century, Francisco Capelo Collection

PT: Japão, Ogata Kenzan, início de século XVIII, Coleção Francisco Capelo