by Elisabetta Colla, FLULisboa

Museum: Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau

Inventory No.:1538 to 1557

Name: Procession

Author: Unknown

Place of Execution: China

Dating: Ming dynasty (1368-1644) century AD

Material: Painted earthenware

Dimensions – from left to right (cm): 28 x 9 x 7; 29 x 10 x 7; 28 x 9,5 x 6,5; 28 x 10 x 7; 29 x 9,5 x 7; 28 x 9,5 x 7,5; 29 x 9 x 7; 29 x 9 x 7; 29 x 10 x 7,5; 29 x 10 x 7,5; 29 x 10 x 7,5; 29 x 10 x 7,5; 29 x 9,5 x 7; 30 x 9 x 7; 29 x 9 x 7; 29 x 9,5 x 7; 28,5 x 9 x 7;28 x 10 x 7; 29 x 9,6 x 7. Palanquin: 24 x 12 x 13,5.

These polychrome-glazed pottery figurines depict a miniature ensamble of a funerary procession. They belong to the permanent collection exhibited at the Museu do Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau (Macau Scientific and Cultural Centre – CCCM, I.P.) in Lisbon. The Museum of the Centre, which has a “twin institution” in Macau, houses an assortment of about 3,000 objects. These artefacts, distributed on two floors, are made of diverse materials and belong to different periods, which span from the Neolithic time to the twenty-first century. The building that hosts the Museum, the Research Centre and the Library was used by the Red Cross during World War I and became headquarter of the nation’s ex-servicemen’s organisation, the Portuguese Legion. After 1974, the building was used to house refugees from old Portuguese colonies. When the building was chosen to host the Macau Scientific and Cultural Centre, the renovation project was conceived by Paulo-Guilherme Tomáz Dúlio Ribeiro D’Eça Leal (1932 – 2010) (vide CCCM, I.P.).

A permanent exhibition is displayed on the two lower floors of the renovated four-storey building of the Centre. On the ground floor, visitors are welcomed by the bust of the tycoon Stanley Ho (何鴻燊; 1921 – 2020), on the left there is a tiny cafeteria, with a beautifully carved wooden panel probably of the Qing dynasty. The first part of the permanent exhibition is constituted by maps, books and artefacts made of various materials (terracotta, porcelain, wood, bronze and textiles) and is organised in order to provide a reconstruction of the history of Macau from the 16th century up to the handover, which occurred on 20 December 1999. On the same floor, a unique scale model of a “Black Ship” (“Nau do Trato” or kurofune 黑船), gives to the visitors the opportunity to immerse themselves into an imaginary journey along the maritime trade routes during the age of exploration, which are also displayed in interactive maps. Two guardian lions at the bottom of beautiful wooden stairs give access to the first floor where one has the chance to admire five thousand years of Chinese art. Highlights of the collection are the Museum’s shiwan ware (石灣窯), one of six known “Jorge Alvrz [Álvares] bottles” made of porcelain with underglaze blue, oil paintings on Macau landscapes and “Thomas Pereira”, gouache on paper by the contemporary artist and collector José de Guimarães (cf. CCCM, I.P.).

The majority of the artefacts displayed in the permanent exhibition comes from António Sapage’s collection. António Manuel dos Santos Sapage was born in Macau on January 26, 1949. From a very young age, he had demonstrated a specific interest in studying and collecting Chinese art. He had soon accumulated a long experience in Asian art and turned Macau in one of the world’s main centres for the exchange of artworks from Asia. His activities were well known in New York, London, Amsterdam, Monaco, Hong Kong, P. R. China and Portugal. He was nominated vice-chairman of the Association of the Collectors of Macau (Associação dos Coleccionadores de Macau), honorary and permanent director of the Association of Experts and Collectors of Chinese Antiquities of the Guangdong Province (Peritos e Coleccionadores de Antiguidades Chinesas da Província de Guangdong), and he became member of the Hong Kong Museum Society and of London’s Oriental Ceramic Society. For this reason and for his commitment to the promotion of the collection, study and knowledge of Chinese art in Macau, as well as for his role in triggering the internationalisation of Macau as privileged art market for collectors of Asian art, on 27 September 1999, he was awarded with the medal of Cultural Merit by Governor Vasco Rocha Viera (art. 7º, Decreto Lei nº 42/82/M, cf. Boletim).

Funerary procession. Cortejo funerário.

©Macau Scientific and Cultural Centre, I.P.

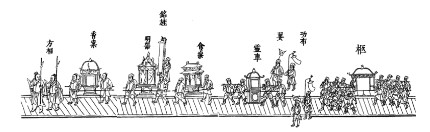

On the ground floor of the Museum, at the entrance, lies the funerary procession protected by a glass box. This incomplete set is of unknown authorship and it is estimated to have been manufactured in China during the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644 CE) (CCCM, I.P.). At first glance, even an inexpert eye notices that some pieces as well as some accessories are missing (i.e. banners, musical instruments, horses, among others). This aspect is confirmed by the beautiful iconographical reconstruction of a funerary procession depicted in the “Master Zhu’s family rituals” Jiali yijie 家禮儀節 (1608) attributed to Qiu Jun 邱濬 (1421–1495 CE) (apud Zhu; Ebrey, 1991: 118-119). This iconography can suggest, although cannot be understood as a fixed pattern, the distribution of the burial figurines (mingqi 明器) extant in the procession. Mingqi, which literally means “bright goods,” were popularised during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) and continued to be produced over time, providing not only details on the worldly life, but also insights into afterlife (Colla, 2012: 181). Together with other funerary structures (i.e. spirit-road sculptures pathways), they aimed at performing the deceased social role, beside ensuring the well-being of the dead, which was pivotal for the harmonious living of all those the dead left behind.

Depois de Funeral Procession in Jiali yijie 家禮儀節 vol. 5 juan 卷 54a-b (apud Zhu; Ebrey, 1991: 118-119). Adaptada pelo autor.

A funeral was perceived as a religious and social event that mediates between the individual, the family, and the community, imbued with diverse socio-political elements. Since the implementation of the complex system of Zhou death rituals, which were simplified by Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200 CE) in his Family Rituals (Zhu; Ebrey, 1991) in the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE) and further reformed in the following dynasties, one witnesses the bureaucratisation of the afterworld.

Because the sphere of ancestral influence was considered closer to the lives of their immediate descendants, funerary ritual practices followed the extant social hierarchy and they were considered a powerful means for constructing and consolidating social relations among the living. The funeral was seen as an opportunity to reaffirm social status and networks, but also to prevent possible injuries caused by evil spirits through offerings to deities and ancestral spirits.

Therefore certain rituals were performed and protective spells pronounced, written down, and buried in the tomb, which starting from the first century had become the lieu of ritual offerings for the deceased, substituting the previous temples. Long processions escorted the coffin to the burial ground and the ceremony of interment passing through a the “spirit pathway” (shendao 神道) flanked by huge and large stone statues, which antecedes the burial ground. These kind of artefacts show the need to materialize a system of mutual dependence between the living and the dead, which is also common in other East Asian systems.

Funerary processions, as those depicted in the Jiali yijie (Qiu; Yang; Zhu, 1608; Zhu; Ebrey, 1991: 118-119), are just a fragmentary picture of the whole scenario. This includes: Exorcists (fangxiang 方相), Incense Altar (xiang’an 香案), Grave Goods (mingqi 明器), Funerary Streamer bearing the title of the deceased (mingjing 銘旌), Food Table (shi’an 食案) and finally the Soul Carriage (lingche 靈車) precede the coffin (jiu 柩) accompanied by Shades Streamers (sha 翣 and gongbu 功布). These objects did not only depict the funerary procession per se, but were also believed to possess innate powers that ‘made clear’ the separation between the dead and the living as suggested by Xunzi (ca. 310–215 BC) (Lagerwey; Kalinowski, 2009: 9) and the way to express the sorrowful feelings (ai 哀) of the mourner (Cook, 1997: 18). In the fourth and longest chapter of Zhu Xi’s Family Rituals we can read: “[w]hen the coffin travels, the male and female mourners, from the presiding ones on down, walk behind it, wailing. The seniors come after the other mourners, followed by relatives without mourning obligations, then guests. Relatives and friends set up a tent beyond the city wall on the side of the road as a resting place for the coffin; they make an oblation there. On the road, the mourners wail whenever grief is felt” (Zhu, Ebrey 1991: 67).

However, this was neither a fixed distribution of performers, nor the model applied to each funeral. Historical implementations, religious believes and other elements affected these rituals, which were also influenced by local customs and historical times. Therefore, these mingqi depicting funerary processions of the Ming dynasty represent a preoccupation to fix any minute detail of ritual action based on social hierarchy in order to show the status of the deceased person, to show filial piety (xiao 孝), as well as to keep harmony between the living world and the afterlife sphere. In sum, they are a simulacrum with a powerful cathartic dimension (Colla, 2012: 181) aimed at mediating mourning and grief.

Acknowledgements: Carmen Amado Mendes (President of the CCCM, I.P.) and Rui Abreu Dantas (Coordinator of the Division of Museology, CCCM, I.P.)

Bibliography and useful links:

“António Sapage”, Museum of the CCCM, I.P. [18 January 2023] https://www.cccm.gov.pt/en/museum/antonio-sapage/.

Barreto, Luís Filipe; Maria Manuela d’Oliveira Martins and Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau. 1999. Guia Do Museu Centro Científico E Cultural De Macau. Macau: Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologia.

Barreto, Luís Filipe Alexandra and Costa Gomes “Criação do Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau – CCCM – Uma breve apresentação.” Suplemento – Revista Oriente Ocidente Ns. 33 e 34 II Série (2016-2017), pp. 1-11, [18 January 2023] https://issuu.com/iimacau.

Boletim Oficial de Macau – I SÉRIE – nº 39-27-9-1999, [18 January 2023] https://images.io.gov.mo/bo/i/99/39/pt-350-99.pdf

CCCM, I.P. – Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau, site: https://www.cccm.gov.pt/en/

Clunas, Craig. 2007. Empire of Great Brightness: Visual and Material Culture of Ming China, 1368–1644. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Colla, Elisabetta. 2012, ““Animism, Magic and the Omnipotence of Thought”: Ritualistic Artefacts and Mourning Mediation in Imperial China”. Panic and Mourning: The Cultural Work of Trauma, edited by Daniela Agostinho, Elisa Antz and Cátia Ferreira, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 181-192. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110283143.181.

Cook Scott. 1997. “Xun Zi on Ritual and Music.” Monumenta Serica 45 (1997) S. [1] pp. 1 – 38.

Ebrey, Patricia Buckley. 1991. Confucianism and Family Rituals in Imperial China: A Social History of Writing about Rites. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lagerwey John and Marc Kalinowski, eds. 2009. Early Chinese Religion Part One: Shang through Han (1250 Bc-220 Ad). Leiden: BRILL.

Rawski, Evelyn Sakakida and James L Watson. 1988. Death Ritual in Late Imperial and Modern China (Studies on China; 8). University of California Press.

Sapage, António Manuel dos Santos; Maria Alexandra da Costa Gomes and Palácio de Queluz (Museum : Queluz Portugal). 1994.Do Neolítico Ao Último Imperador: A Perspectiva De Um Coleccionador De Macau. Macau Lisboa: Governo de Macau; Instituto Português do Património Arquitectónico e Arqueológico.

Sapage, António. 1992. Porcelana Chinesa De Exportaçaõ : Diálogo Entre Dois Mundos = Zhongguo Wai Xiao Ci : Zhong Xi Hui Cui. Macau: Galeria de Leal Senado.

Sapage, António; José Carlos Morais; Weichi Zhang: Museu Luís de Camões. 1995. Shiwan Selecção De Obras Da Colecção Do Museu Luís De Camões; a Selection of Works from the Colection Collection of the Luís De Camões Museum; 27 De Setembro De 1995 = Shiwan-Cuizhen. (Location: Press – no data available).

Sapage, António. 1989. “Porcelana No Comércio Luso-Chinês.” Oceanos N. 14 (jun. 1993) pp. 31-38.

Qiu Jun 丘濬; Yang Tingyun 楊廷筠 and Zhu Xi 朱熹. 1997. Rituals of Wen gong’s [Zhu Xi] Family Rituals [Wengong jiali yijie 文公家禮儀節] (1608). Jinan: Qilu shushe chubanshe.

Zhu Xi and Patricia Buckley Ebrey. 1991. Chu Hsi’s Family Rituals: A Twelfth-Century Chinese Manual for the Performance of Cappings, Weddings, Funerals, and Ancestral Rites. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Estas figuras tumulares de cerâmica policromada, que pertence à coleção permanente do Museu do Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau em Lisboa, representam um conjunto de uma procissão funerária em miniatura. O Museu do Centro, que tem uma “instituição gémea” em Macau, conserva um acervo de cerca de 3.500 objetos. Estes artefactos feitos de diversos materiais estão distribuídos por dois pisos e pertencem a diferentes períodos, que vão desde o Neolítico até ao século XXI. O edifício onde se encontram instalados o Museu, o Centro de Investigação e a Biblioteca era a antiga sede da Cruz Vermelha Portuguesa. Quando o edifício foi escolhido para acolher o Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau, foi realizado um projeto de reabilitação que esteve a cargo de Paulo-Guilherme Tomáz Dúlio Ribeiro D’Eça Leal (1932 – 2010) (vide CCCM, I.P.).

O edifício de quatro andares do Centro acolhe nos dois andares inferiores uma exposição permanente. No rés-do-chão, os visitantes deparam-se com o busto de Stanley Ho (何鴻燊; 1921 – 2020) e, entrando, encontram à esquerda uma pequena cafetaria com um belo painel de madeira entalhada provavelmente da dinastia Qing. Sempre no rés-do-chão, o acervo da exposição permanente é caracterizado por mapas, livros e artefactos feitos de diversos materiais (terracota, porcelana, madeira, bronze e têxteis), que estão organizados de forma a proporcionar uma reconstituição da história de Macau desde o século XVI até a transferência da soberania, que ocorreu no dia 20 de Dezembro de 1999. No mesmo piso, uma reprodução em escala da “Nau do Trato” (“Navio Negro” ou kurofune 黑船) proporciona aos visitantes uma oportunidade única de mergulharem numa viagem imaginária ao longo das rotas comerciais marítimas da época das explorações, que são também exibidas em mapas interativos. Ao pé de belas escadas de madeira que dão acesso ao primeiro piso, no qual se pode admirar cinco mil anos de arte chinesa, encontram-se dois leões guardiões. Da coleção do Museu destacam-se as cerâmicas shiwan (石灣窯), uma das seis conhecidas “garrafas Jorge Alvrz [Álvares]” em porcelana branca decorada a azul-cobalto sob o vidrado, as pinturas a óleo com paisagens de Macau, e “Thomas Pereira”, um guache sobre papel do artista contemporâneo e colecionador José de Guimarães (cf. CCCM, I.P.)

A maioria dos objetos da exposição permanente provem da coleção de António Sapage. António Manuel dos Santos Sapage nasceu em Macau a 26 de Janeiro de 1949. Desde muito jovem demonstrou um interesse específico em estudar e colecionar arte chinesa. Em pouco tempo acumulou uma grande experiência na arte asiática e transformou Macau num dos principais centros mundiais de intercâmbio de obras de arte asiáticas. As suas atividades eram bem conhecidas em Nova Iorque, Londres, Amsterdão, no Mónaco, em Hong Kong, na R. P. da China e em Portugal. Chegou a ser nomeado vice-presidente da Associação dos Colecionadores de Macau e diretor honorário e permanente da Associação dos Peritos e Colecionadores de Antiguidades Chinesas da Província de Guangdong, e tornou-se membro da Hong Kong Museum Society e da Oriental Ceramic Society de Londres. Por este motivo e pelo seu empenho na promoção da coleção, estudo e conhecimento da arte chinesa em Macau, bem como pelo seu papel no desencadeamento da internacionalização de Macau como mercado privilegiado de arte para colecionadores de arte asiática, no dia 27 de Setembro de 1999, foi agraciado com a medalha de Mérito Cultural pelo Governador Vasco Rocha Vieira (art. 7º, Decreto Lei nº 42/82/M, cf. Boletim).

À entrada do Museu, no rés-do-chão, encontra-se o cortejo fúnebre protegido por uma vitrine. Este conjunto de figurinhas, de autoria desconhecida, encontra-se incompleto e estima-se que tenha sido fabricado na China durante a dinastia Ming (1368 – 1644 dC) (CCCM, I.P.). À primeira vista, até um olhar inexperiente nota que faltam algumas peças, bem como alguns acessórios (como por exemplo, estandartes, instrumentos musicais, cavalos, entre outros). Trata-se de um aspeto que poderá ser confirmado comparando com a reconstrução iconográfica de uma procissão funerária retratada nos “Rituais Familiares do Mestre Zhu” – Jiali yijie 家禮儀節 (1608) atribuído à Qiu Jun 邱濬 (1421–1495 EC) (apud Zhu; Ebrey, 1991: 118-119). Esta iconografia, embora não possa ser entendida como um padrão fixo, pode sugerir como eram distribuídas as estatuetas funerárias (mingqi 明器) do cortejo. Os mingqi, cujo termo significa literalmente “bens brilhantes”, tornaram-se populares durante a dinastia Han (206 a.C.-220 d.C.) e continuaram a ser produzidos ao longo do tempo, fornecendo não apenas detalhes sobre a vida mundana, mas também uma compreensão sobre a vida após a morte (Colla, 2012: 181). Juntamente com outros elementos funerários (i.e. as esculturas do dito caminho dos espíritos), os mingqi eram representativos do papel social do defunto, para além de assegurarem o bem-estar dos mortos, que era fundamental para a harmonia de todos os que o defunto havia deixado para trás.

O funeral era encarado como um evento religioso e social, isto é, uma mediação entre o indivíduo, a família e a comunidade, e por isso acabava por ser imbuído de diversos elementos sociopolíticos. O complexo sistema de rituais funerários, implementado durante a dinastia Zhou (1046 AEC – 256 AEC) foi simplificado durante a dinastia Song (960–1279 EC) por Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200 EC) nos seus “Rituais Familiares” (Zhu; Ebrey, 1991). Estes rituais, que foram posteriormente reformados nas dinastias seguintes, representam a burocratização do além.

A esfera de influência ancestral chegava à vida dos seus descendentes mais próximos e as práticas funerárias seguiam a mesma hierarquia social em vigor, pelo que os rituais eram também considerados um meio poderoso para construir e consolidar os laços sociais entre os vivos. O funeral era visto como uma oportunidade para reafirmar a posição de um individuo na sociedade e para consolidar a sua rede de influências, sendo ainda que as oferendas às divindades e espíritos ancestrais eram vistas como uma forma de prevenir possíveis interferências causadas pelos espíritos malignos.

A seguir, eram praticados certos rituais e proclamados feitiços de proteção que, quando escritos, eram enterrados no túmulo, o qual, a partir do século primeiro, se tornaria local de oferendas para os mortos, substituindo-se aos templos correspondentes. As longas procissões que escoltavam o caixão até o cemitério, antes da cerimónia do enterro, passavam por um “caminho espiritual” (shendao 神道) ladeado por enormes e grandes estátuas de pedra. Este tipo de artefactos testemunha a necessidade de materializar a relação de dependência que existia entre vivos e mortos, algo comum a outros sistemas religiosos da Ásia Oriental.

As procissões funerárias, tais como as representadas no Jiali yijie (Qiu; Yang; Zhu, 1608; Zhu; Ebrey, 1991: 118-119), são apenas uma imagem fragmentária de um todo, que inclui exorcistas (fangxiang 方相), um altar para o incenso (xiang’an 香案), artefactos tumulares (mingqi 明器), um estandarte funerário vertical com o título póstumo do falecido (mingjing 銘旌), uma mesa para as oferendas alimentares (shi’an 食案) e, finalmente, uma carruagem da alma (lingche 靈車) que precede o caixão (jiu 柩) acompanhada por leques rituais e fitas (sha 翣 e gongbu 功布). Esses acessórios não eram apenas parte da procissão funerária per se, mas acreditava-se que possuíssem poderes sobrenaturais inatos capazes de manter separados os mundos dos vivos e dos mortos, como indicado por Xunzi (ca. 310–215 aC) (Lagerwey; Kalinowski, 2009: 9) e uma forma para expressar os sentimentos de tristeza (ai 哀) dos enlutados (Cook, 1997: 18). No quarto e mais longo capítulo dos Rituais Familiares de Zhu Xi, podemos ler: “[quando] o caixão é transportado, mulheres e homens enlutados marcham atrás deles num lamento, aos que presidem, seguem todos os outros. Os mais velhos precedem os outros enlutados, seguidos pelos parentes sem obrigações de luto e finalmente pelos convidados. Para abrigar o caixão, os parentes e amigos instalam uma tenda fora das muralhas citadinas, à beira da estrada, onde fazem uma oblação. Ao longo de todo o caminho, o cortejo continua em lamento do seu pesar” (Zhu, Ebrey 1991: 67)

No entanto, esta distribuição de figurinhas não é fixa, nem poderá ser entendida como modelo para todos os funerais. As práticas históricas, as crenças religiosas e outros elementos influíram sobre estas procissões, que foram também influenciados por costumes locais e momentos históricos. Portanto, esses mingqi que representam procissões funerárias da dinastia Ming representam uma preocupação em fixar qualquer detalhe minucioso da ação ritual baseada na hierarquia social, a fim de mostrar o estatuto da pessoa falecida, evidenciar a piedade filial (xiao 孝), e ainda manter a harmonia entre o mundo dos vivos e a esfera da vida após a morte. Em suma, são um simulacro com uma poderosa dimensão catártica (Colla, 2012: 181) destinado a mediar o luto e o pesar.

Agradecimentos: Carmen Amado Mendes (Presidente do CCCM, I.P.) e Rui Abreu Dantas (Coordenador da Divisão de Museologia, CCCM, I.P.)