by Maria Szymańska-Ilnata

The exhibition “Created with Sound” follows from years of musicology research carried out by the Asia and Pacific Museum. Its first result was the Sound Zone – the permanent display opened in 2016. Devised by the same curator, Dr Maria Szymańska-Ilnata, this temporary show comments on and complements its predecessor. [Maria Szymanska, Created With Sound. Music and Dance in Visual Arts of Asia and Oceania (2023), https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22360207.v1.]

This multisensory exhibition tries to determine whether the available artistic techniques are potent enough to capture and freeze the fleeting phenomena of music and dance. It also wants to find out if visual artworks with musical subjects can be useful to researchers studying the musical culture and its development. The display includes around 170 exhibits from the Asia and Pacific Museum’s collection, hailing from different countries of Asia and Oceania, created by artists with different backgrounds, using various techniques and materials. A separate section of the exhibition shows works by Polish artists inspired by the music and dance of Asia and Oceania. Visitors will see art by Nyoman Gunarsa, K.K. Hebbar, Andrzej Kobzdej, Roman Opałka, Andrzej Strumiłło, and more.

The exhibition ‘Created with Sound’ starts with a historical introduction that covers reproductions of some of the oldest depictions of musicians and dancers hailing from Asia. It then goes on to discuss different groups of musical instruments and dances explored by Asian visual artists who were active mostly in the 20th century. Next, it explores the cultural contexts in which music and dance function in different communities, focusing in particular on such aspects as religion, festivities, everyday life, war, and hunting. The last part is dedicated to the work of Polish artists inspired by Asian performing arts.

Executed in various techniques (paintings, drawings, sculptures, paper cuts), artworks with musical subjects are a testament to the role that music and dance play in culture. While some are artistic visions loosely connected with reality, others are documents that record situations witnessed by the author and can serve as sources of knowledge for historians, musicologists, sociologists, and philosophers. Achievements of all of these disciplines are taken into account by researchers involved in the study of depictions of music and dance in visual arts, or musical iconography.

When analysing and comparing works of visual arts created over the course of centuries, we can track changes in instrument construction and composition of ensembles, and determine which of the contemporary musical traditions have the longest history.

Each part of the display focuses on a different topic. The selection of exhibits from some of them is presented below:

Hailing from India, the sculpture of a man with a bear and an hourglass drum is a reference to a once-popular kind of entertainment. It depicts a member of the nomadic Kalandar community that specialised in taming wild animals and selling their organs, which were subsequently used to produce medicaments and amulets. The sculpture reveals a lot of details concerning bear dancing in India. The tamer controls the animal using a stick with a rope tied to the bear. The sounds of the drum held by the man in the other hand are supposed to accentuate the bear’s ‘dance’ moves and create the impression of enjoyment. The cruel entertainment is fortunately on its way out. Let us hope that soon dancing bears will become a relic of the past seen only in museums.

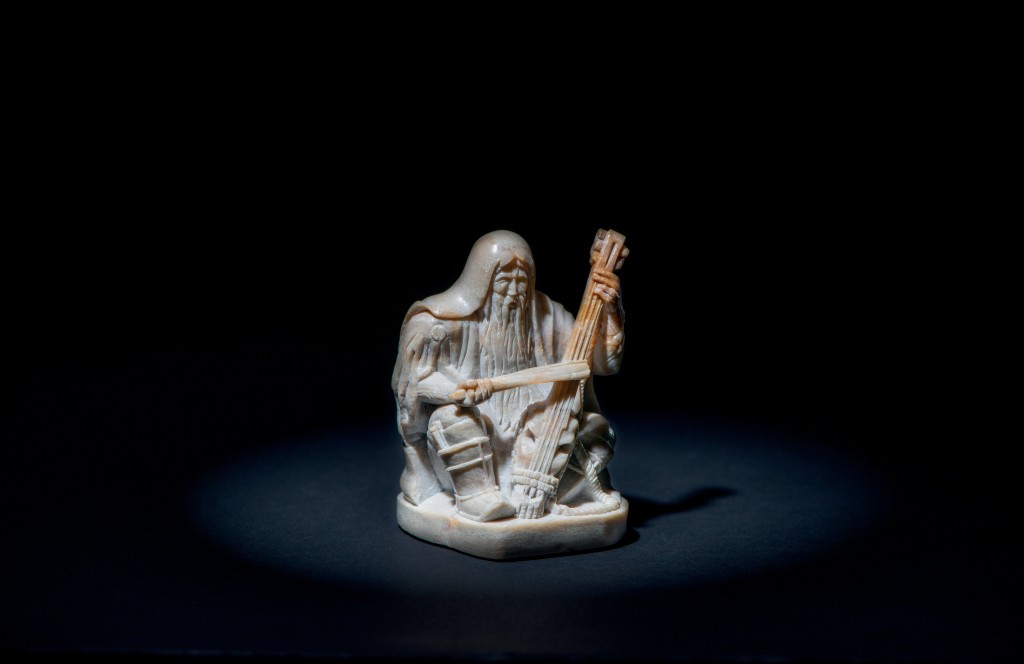

Carved in stone, the long-bearded man vertically holds an instrument with a long neck and clearly executed tuning pegs. The instrument, which could be the igil, cannot be identified for certain. Rendered with striking precision, the bow hold is completely different from the European practice. Other interesting details are the player’s focused facial expression or his footwear, which is characteristic of the craftwork in its region of origin.

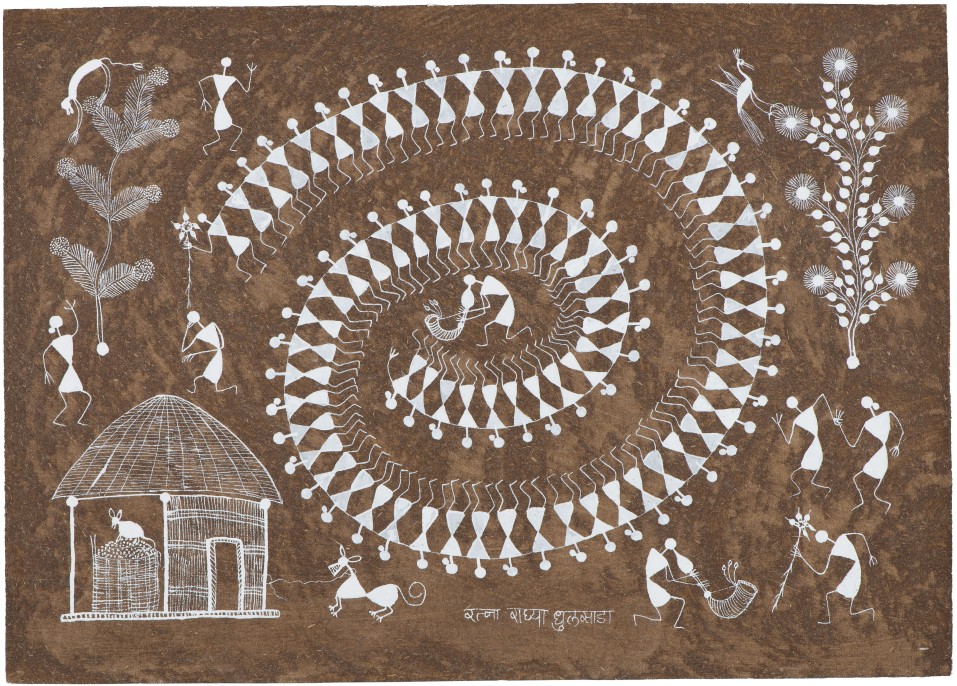

In this work Indian painter K. K. Hebbar captured a male musician playing the tarpa, an instrument used by the Warli people of southern India to mark festivities such as the end of harvest. The tarpa consists of a gourd and a flared bell made from a rolled leaf. Hebbar was born into a family of artists and studied painting. He developed his own style, while also drawing from local traditions and experiences gained when studying in Europe. He travelled across India, watching and subsequently portraying musicians and dancers.

At first glance, it is hard to spot the musical instrument in the bottom left corner of the woodcut. It is the qing, a lithophone, or an instrument consisting of stone slabs of the same size but different thickness. In the Chinese language there are many words that have different spellings and meanings, but are pronounced the same, as is the case with lithophone and celebration. For this reason, the instrument is frequently depicted in woodcuts conveying best wishes for such occasions as the New Year, alongside other symbols of good luck and protection, such as the cock. [Welch, ‘The Symbolism of Chinese Musical Instruments in Chinese Art: When a Zhu is more than a Zither’, 95.]

The painting by Alphonse Kauage, a well-known contemporary painter from Papua New Guinea, bears the following pidgin language inscription: ‘Ol mangi Nakondi amasmas na Kalap Kalap wantain Ol mangi South long Morobe Show’ [The young from Nakondi have fun and jump (dance) together with the young from the South at the Morobe Show]. [Translated into English based on a Polish translation by Fr. J. Jaworski.] The Morobe Show is an annual event held since 1959. It includes dance performances by representatives of Papuan local communities in traditional dress. The painting depicts one of such performances, featuring pink-painted inhabitants of the village of Nakondi and representatives of the Asaro Mudmen group, whose costume draws on a legend of mud-covered Asaro warriors being mistaken for spirits and thus defeating their enemies. [Ton Otto and Robert J. Verloop, ‘The Asaro Mudmen: Local Property, Public Culture?’, The Contemporary Pacific 8, No. 2 (1996): 353.]

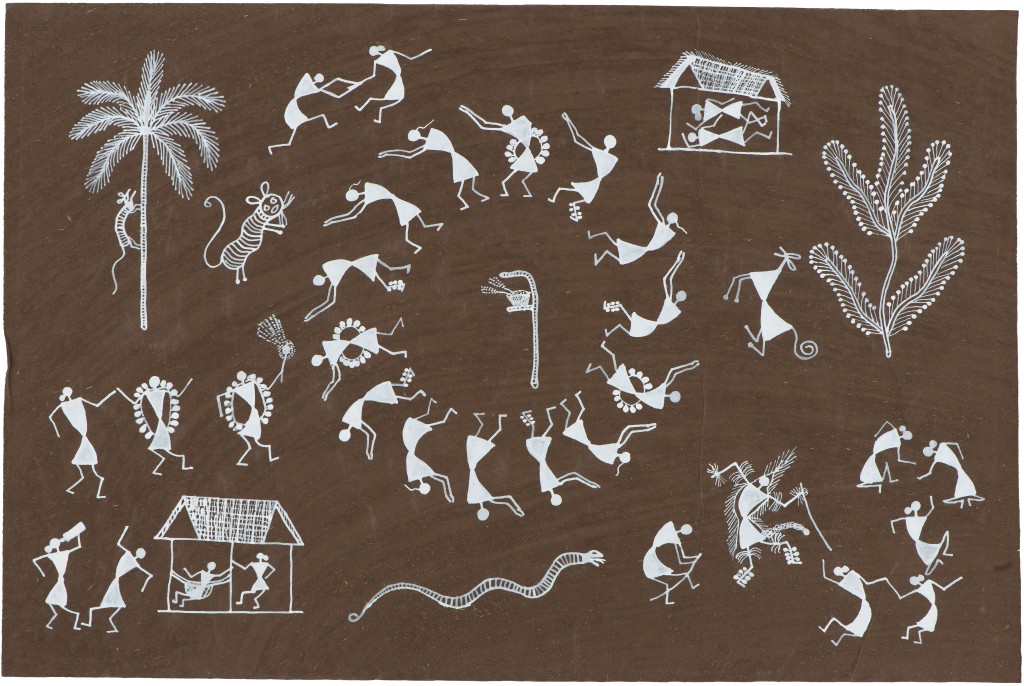

The Warli people did not take advantage of technological advances, living instead in accordance with the traditions of their ancestors. They led a semi-settled life, lived in windowless huts, cultivated land and raised animals. To mark weddings and harvests, women would decorate the interiors of the huts with paintings depicting scenes of ordinary life and religious symbols. They executed them solely with white paint made from rice flour. [Lakshmi Lal, ed., The Warlis: Tribal Paintings and Legends (Bombay–London: Chemould Publications and Arts, 1983), 4.] In the 1970s, as part of a governmental programme aimed at supporting impoverished communities, the Warli were supplied with brown paper and white acrylic paint so that they could turn their art into a source of income. As a consequence, some of the artists gave up the traditional, religious subjects to focus on capturing their own life. It was then that men took up painting, too, including Jivya Soma Mashe, who turned out to be a remarkable personality and soon received numerous commissions. This way, Warli painting made its way to the European market and gained popularity. The pieces possessed by the Asia and Pacific Museum are depictions of festive dancing. The first illustrates end-of-harvest celebrations as evidenced by the fact that the participants dance around a basket full of cereal crops. The other painting shows the Diwali festival: a musician playing the tarpa is pictured in the centre, with a procession of dancers winding behind him. In the bottom right corner, you can see another tarpa player and a man carrying a cane, perhaps performing a religious function.

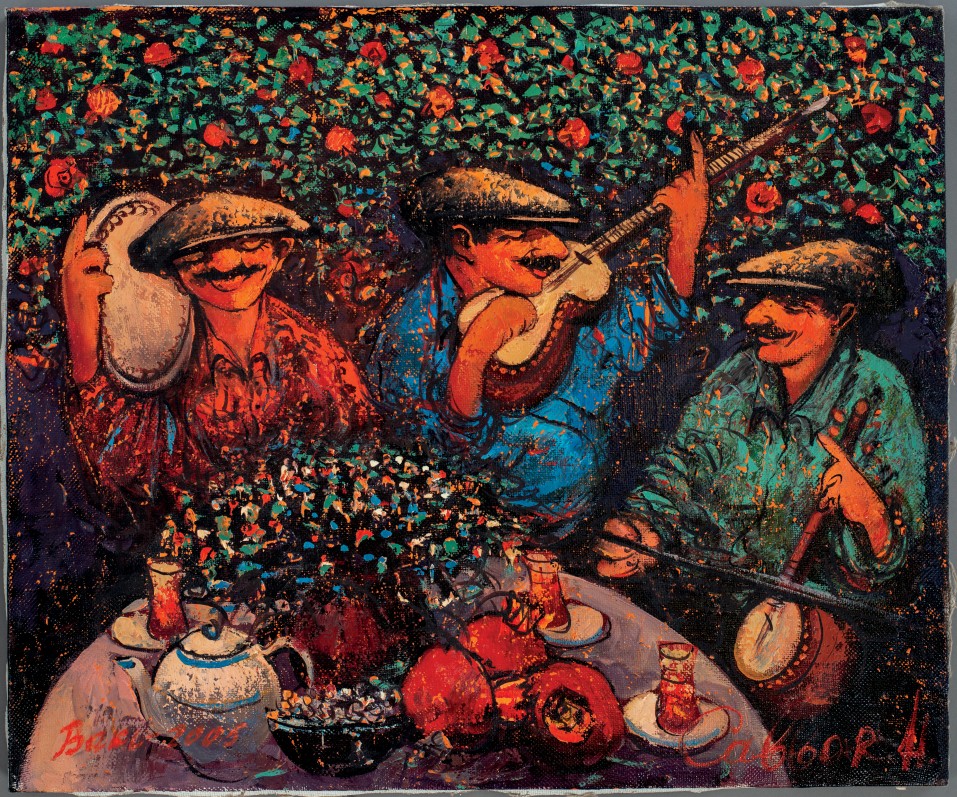

Sitting at the table surrounded by greenery, the three musicians hold traditional Azerbaijani instruments. The first one is the gaval, a frame drum with jingles more widely known under its Persian name of daf. The second one is the tar, a plucked lute with a waisted resonator, while the third is the kamancheh, a bowed lute with a circular resonator. The performers take joy in playing music together. You can see them smiling with their eyes closed – they are savouring the moment of music-making over evening tea.

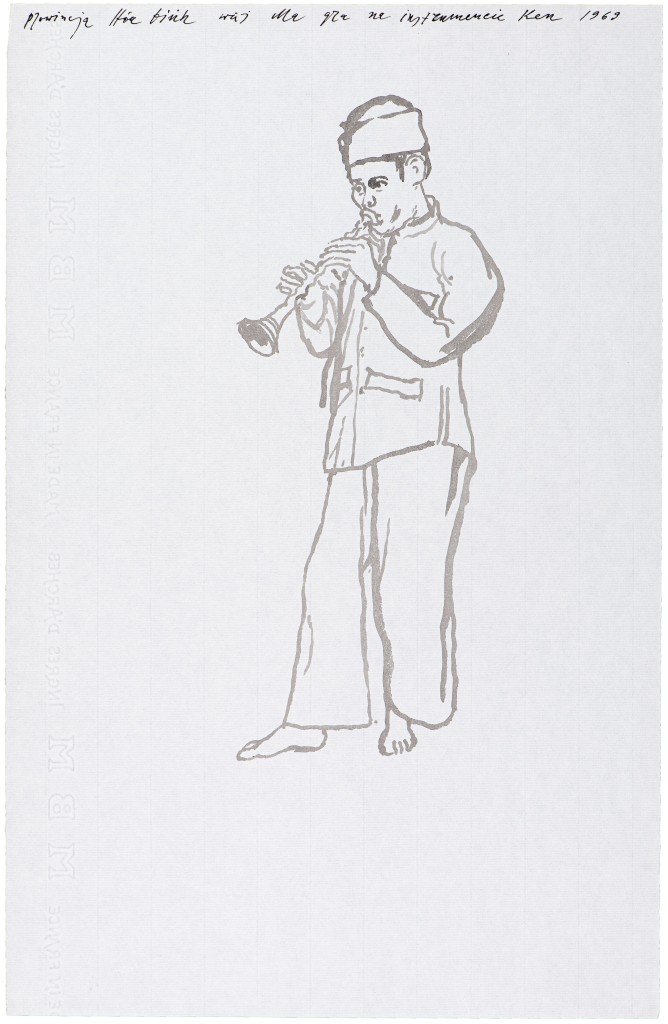

In the wake of his journeys to Asia, Andrzej Strumiłło created numerous artworks inspired by the continent, including drawings exploring musical subjects. Many come with notes and comments that greatly facilitate their interpretation. The drawing of a shawm player clearly shows the disc that allows the player to rest his lips. Thanks to a note written near the upper edge of the work, which reads ‘Hoa Binh province, Waj Ma plays the ken 1969’, we know the local name of the instrument and the name of the player.

The exhibition includes six interactive stands which encourage visitors to take part in creative activities and test the knowledge gained at the display. Two audio guides – for children and adults – are available, as well as audio descriptions and tactile graphics for anyone who needs it. The catalogues in Polish and English can be downloaded from the website: https://www.muzeumazji.pl/maip/uploads/2022/09/created-with-sound_album.pdf

The exhibition has been curated by Maria Szymańska-Ilnata.

Maria Szymańska-Ilnata – curator at the Asia and Pacific Museum in Warsaw, responsible for the collection of musical instruments and Indonesian artefacts. She graduated in Musicology and Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology at Warsaw University. She studied traditional Javanese dance and music at the Institute of Indonesian Arts (ISI) in Surakarta, Indonesia. She holds a PHD in musicology from the Polish Academy of Sciences. She conducted a project entitled “Musical culture of Sumatra in the light of historical sources and contemporary field research” (2014-2017) funded by the National Science Centre as a part of the Prelude 5 Programme. She prepared two parts of the permanent exhibition at the Asia and Pacific Museum: the “Sound Zone” devoted to musical culture and instruments from many countries of Asia and Oceania, and the Indonesian Gallery.