On 18 April 2023, ACN – Europe held the online workshop “East Asian ‘Orphaned’ Objects in Slovenia: How to Determine Provenance”. The speakers, who are conducting research within the national project “Orphaned Objects: Examining East Asian Objects outside Organised Collecting Practices in Slovenia” (2021-2024), explained how and why a number of East Asian objects in Slovenian collections are accompanied by scanty records about their origins and acquisition history. Consequently, they illustrated what can be done to research their provenance when only sparse documents are preserved.

Bronze incense burner, Meiji period, Japan, Asian and South American Collection, Celje Regional Museum.

Nataša Vampelj Suhadolnik, Professor at the Department of Asian Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, opened the workshop with an excursus on the concept of “orphaned objects”. Borrowed from archaeological and art-historical theory, this definition was, in fact, originally applied to three categories of artefacts: those that are fragmented; those whose historical contexts is unknown; and those that are excluded from museum display due to various selection criteria. Nataša, then, went on presenting the complex socio-political circumstances that in Slovenia led to the loss of the history of East Asian orphaned objects. These initially emerged in 2018 within the scope of the national research project East Asian collections in Slovenia, which started to systematically examine five Slovenian collections of objects left as legacy of missionaries, sailors and travellers. The analysis of these collections revealed that the objects that are mostly affected by the lack or scarcity of documentation can be grouped in specific typologies: items confiscated during the Nazi occupation and the Communist regime and put in museum storage until recently; items in Slovenian castles and manors which were part of the aristocratic heritage and were gradually dispersed before and after the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian empire; items brought by sailors, for which contextual and technical information is missing. The mechanisms that led to the loss of information have also been identified. In some cases, the objects were sold by impoverished nobles or were given away as inheritance or gifts. In other cases, the objects were amassed in Collection Centres and eventually considered to be state property. Transferred between private and public sphere and between public institutions in the backdrop of continuously changing political situations, East Asian objects were often neglected and forgotten. They were not deemed relevant to national cultural heritage and were depleted of their larger historical and geographical contexts according to a nationalist perspective limiting research to the boundaries of nation-states. They fell victims of oblivion and decay also because of the lack of specialist knowledge about East Asian cultures among museum staff due to contingent limitations and deliberate ideological choices.

Nataša concluded by recognising that these orphaned objects present a unique challenge that raises questions not only about their own unknown biography, but also about methodological approaches when dealing with missing information.

Her colleagues Davor Mlinarič, curator of the Asian and South American Collection at the Celje Regional Museum, and Helena Motoh, Senior Research Associate at the Institute for Philosophical Studies of the Science and Research Centre Koper and Assistant Professor at the Department for Asian Studies of the Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, continued the presentation with two case studies. Highlighting different aspects of the methodological approaches to determine the provenance of orphaned objects, they focused on two objects, both from the Asian and South American Collection of Celje Regional Museum.

Japanese chest armour dō 胴, Edo period, Japan, Asian and South American Collection, Celje Regional Museum.

Davor illustrated the successful case of how he managed to reconstruct the history of a Japanese samurai armour. He explained that only basic information about this object arrived after World War II from the Celje Collection Centre housed in the Capuchin monastery that the Nazis used to store objects they confiscated in the Celje area during occupation. With the help of historical archives and lists of confiscated objects, Davor traced the provenance of this armour Schloss Sternstein, in Lower Styria (today in Slovenia). This was the manor of the British Faber family, which had been taken by the Nazis with all its contents in 1941-42. Inventory sources also allowed to ascertain that under the Communist regime, the armour and other items were moved from the Capuchin monastery, that in the meantime, had become the Celje Federal Collection Centre, to the Celje Regional Museum and in 1964, it was eventually included in a separate collection of Asian and South American objects.

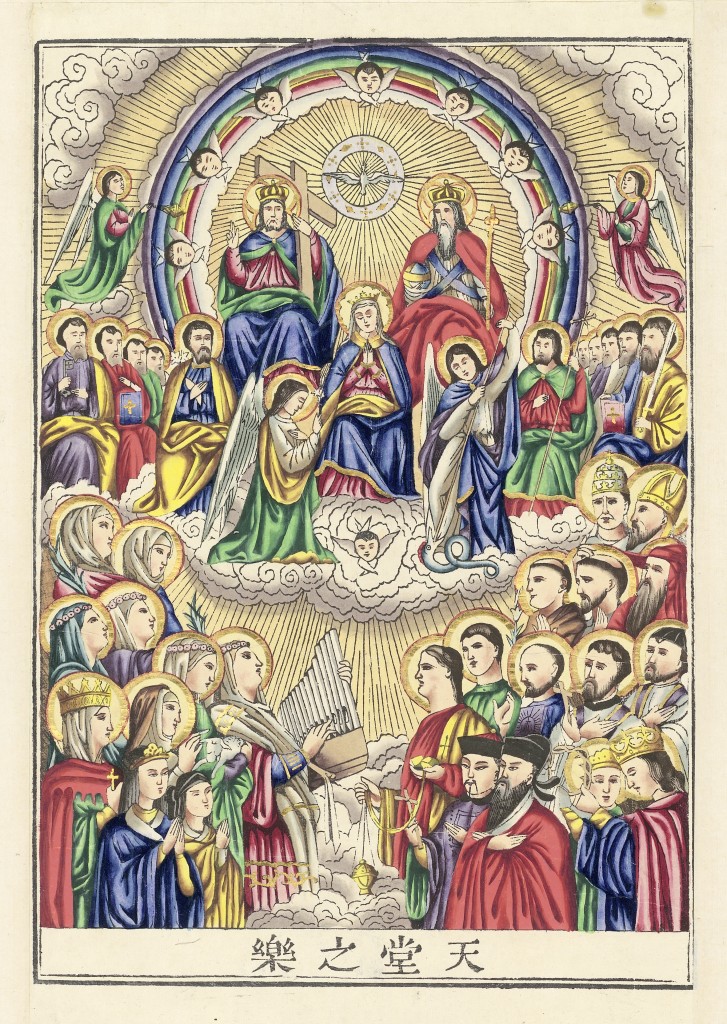

Image from a missionary print scroll, 2nd half of the 19th century, most probably from Tushanwan workshops, China, Asian and South American Collection, Celje Regional Museum.

The case study presented by Helena was an example of an investigation that so far has not been successful and has led to a dead-end. The object analysed was a 19th century missionary scroll made of hand-painted woodcut prints from Adolphe Vasseur’s “All Images Depicting the Deeds of the Saviour” (first published in 1869) pasted on silk base. A pencil inscription in German mentioning a missionary centre near Shanghai and the date 1883 provided the clues that allowed to identify the place of origin as the Xujiahui Jesuit centre with its workshops where orphans were trained to various crafts. The scroll was also inventorised in 1964 in the Celje Regional Museum among the objects coming from the District Collection Centre. However, all the history in between remains unknown. Helena has therefore attempted to reconstruct the missing biography by approximation, hypothesising different possible scenarios. In scenario A, among the people who had been in China from Slovenia, she singled out Joseph von Haas, diplomat and interpreter for the Austro-Hungarian consulate in Shanghai in 1869. When he died in 1896, his widow moved back to Europe taking with her the couple’s collection, to which the scroll maybe belonged. In 1913, she settled in Mozirje, a village near Celje, and when she died in 1943, the collection was dispersed and perhaps partially confiscated.

In scenario B, Helena suggested that the object could have been confiscated from Alma Karlin, who travelled around the world in 1919. She stayed in Shanghai in 1923 and in her diaries she wrote that she bought objects from the Jesuit orphanage and workshop. Her house near Celje was confiscated in 1945, along with some of her possessions. The rest of her collection was included in the Celje Regional Museum when she passed away in 1950.

According to Helena the most probable but most difficult to prove is scenario C: the owner could have been a missionary from the Franciscan, Lazarist or Vincentian order. The presence of Slovenian missionaries in China in the early 20th century is documented. It is also known that the Vincentian monastery in Celje was confiscated in 1941 and that with a court order in 1948, all Vincentian properties were seized, including the collections of the missionary museum in Tabor that also housed objects collected by Lazarists and Franciscans.

With no definitive confirmation for any of these scenarios, Helena hopes to find a mention to the scroll in one of the lists of objects attached to confiscation documents.

The main points emerged in the discussion after the presentations are summarised as follows.

- While trying to piece together the fragmentary information about orphaned objects, many histories appear to intersect and play different roles: the travel history of the objects themselves, political history, religious history, the history of collections, the history of individuals and the history of state formation.

- The limitations of nationalist approaches to the study of objects only within the borders of the nation-state allow just for a partial account of the objects’ biographies. Cooperation with researchers in other countries and the possibility to reconstruct the history of orphaned objects following their traces in other countries would greatly improve the chances of obtaining a better picture. This would also help overcome the obstacles of different levels of jurisdiction and the practical issues regarding where the archives are housed.

- Similar cases can be found all over Europe and an open dialogue to compare and connect them could help elaborate methodologies that are more effective in the study of this particular type of objects.

- The history of orphaned objects in Slovenia can potentially leave a bitter taste for both museums and previous owners. When dealing with orphaned objects in Slovenia, researchers sometimes face the reticence and defensive attitude of institutions that find themselves in uneasy and uncomfortable positions, fearing reclamation over objects acquired through channels that were not legitimate.

- A question is finally raised about the general perception of East Asian objects in Slovenian public collections: do Slovenian audiences attribute any particular meaning to this heritage with reference to local history? Some answers to this question might be obtained when orphaned East Asian objects in Slovenian collections will be displayed together in the first ever exhibition that is being prepared about them.

The discussion on this theme will continue in more detail during the International Symposium “Orphaned Objects – Theoretical and Methodological Approaches to the Research of East Asian Objects” that will take place at the University of Ljubljana on 18 September 2023.