The online workshop “Chinese Imperial Carpets in Northern Italy: The Schneiberg Museum”, organised by Asia Collections Network Europe (ACN – Europe), was held on 22 January 2025.

Marco Guglielminotti Trivel (curator and specialist in East Asian art and archaeology with a focus on China) presented an overview of a private collection of a particular type of Chinese carpets.

Sala dei Talismani (Hall of Amulets) – Silk and metal carpets on display at the Schneiberg Museum, Turin. Photo Brigitte Schindler.

While discussing the history and significance of Chinese carpets, particularly those from the Qing period, Marco highlighted the rarity of the typology of the specimens at the Schneiberg Museum, with only around 400 known worldwide, and the scepticism surrounding their imperial status. The Schneiberg Museum in Turin, Italy, which houses this collection of 36 Qing period carpets (representing almost 10% of all the extant carpets of this type), was founded by art dealers Enzo and Roberto Danon, who have a private foundation and a gallery in Rome. The carpets are part of the collection and cannot be sold. The museum’s archives documentation centre aims to gather information about these carpets worldwide. The carpets are certified by the Art Loss Register in London, ensuring their authenticity and preventing theft.

A comparison with some specimens from other collections, such as the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts and the Metropolitan Museum in New York, accompanied the description of the style and decorative composition of the carpets, from which some differences emerged between those of Central Asian inspiration and those with more Chinese influences.

There is also uncertainty surrounding the origins and dates of these carpets, with some attributing them to the Imperial House and others suggesting they were made in the streets of Beijing during the Republican era. Supporting the idea that these carpets were originally made for the Forbidden City and other imperial environments, Marco suggested possible dates for their creation in the late Qing period (19th century) based on specific details, including their materials, dimensions, and inscriptions.

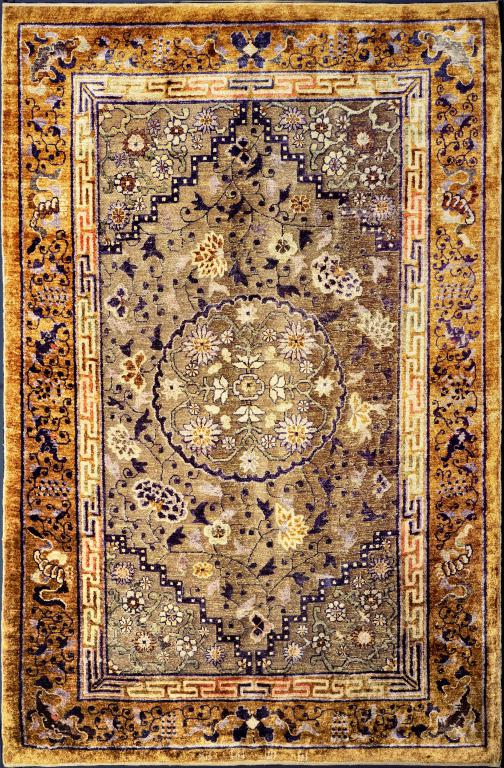

Floral carpet, possibly from the Imperial Workshops of Xinjiang, Qianlong Period (1735-1796). Schneiberg Museum, inv. no. K156. Photo Brigitte Schindler.

At the beginning of the 20th century, this type of carpets were among those often acquired by art dealers and museums worldwide, with the United States being a major collector of Chinese textiles and carpets. They were in fact exposed at the Saint Louis World Exposition in 1904. It even seems to be the case that Emperor Guangxu (1871-1908) had to open a new workshop on Beijing to cope with the increasing foreign demand. In particular, after the dismissal of the Qing Dynasty, many of these carpets were sold to international collectors and dealers. The last Emperor, Puyi, sold a number of these carpets after 1911 and later gave some to the Japanese. However, this type of carpet was not seriously studied in the West until John Haskins wrote a catalogue for the Duke University Museum in 1973.

As for the techniques of weaving, these carpets are made using an asymmetrical knot – typical of China and Central Asia – which brings each of the tuft ends to the surface separately. The use of metal threads in carpets was an innovation originating in Central Asia, transmitted to Xinjiang, Ningxia and Shaanxi and then introduced in Beijing during the 18th century. The metal thread was inserted with the soumak technique, wrapping wefts over a certain number of warps (usually 4) before drawing them back under the last two warps. While still during the Ming Dynasty, carpets were made of wool, it was during the Kangxi period (1661-1722) that silk with or without metal started to be produced at the imperial workshops.

Detail of the background on the border of carpet K156.

Claudio Seccaroni (Research Scientist at ENEA, Laboratory of Technologies and Materials for Additive Manufacturing, in Rome) presented a scientific study on 60 carpets from the Schneiberg Museum and other private collections discussing the materials used to make the carpets, the inclusion of copper, silver and gold threads, and the involvement of zinc in the manufacturing process. While spanning throughout the Qing Dynasty, the carpets in this examination can be mostly attributed to the reigns of Qianlong (1735-1796) – 25 specimens – Jiaqing (1796-1820) – 11 specimens – and Daoguang (1820-1850) – 14 specimens, with the majority (42) produced in Beijing and the rest in Xinjiang (18).

In particular, the non-destructive methods of observation with microscope, X-rays fluorescence spectroscopy and scanning electron spectrography were used for this investigation. The study of the metal threads revealed that the base material was always copper. In four carpets there was only copper, 51 carpets had copper and zinc threads and 5 carpets included threads of copper and silver as well as copper and silver with the addition of gold.

A classification for these carpets is proposed by Marco on the basis of the specimens in the Schneiberg collection. Firstly, this classification takes into account the orientation of the composition: defined or pictorial; advantaged or pseudo-symmetrical; neutral or symmetrical. Secondly, the type of composition is considered: uniform; mixed; medallion; lattice or fretwork (typical of Central Asia). Thirdly, the carpets are distinguished depending on their subject matter, dividing them into: dragons or other auspicious animals; plants and flowers; repetitive patterns within compartments; deities and heavenly settings; and a miscellaneous category including a mixture of subjects and other elements, such as the Summer Palace represented on one of the carpets. In the specific case of the Schneiberg collection, the majority of the carpets feature animals as their central subject.

While there is a lingering prejudice against these carpets, with some scholars and collectors doubting their authenticity and artistic value, there is potential for further study and appreciation of these carpets, which are more than just decorative items, but rather hold symbolic and cultural significance, reflecting the broader Chinese art and culture of the time.

All images: Courtesy of the Schneiberg Museum.