By Marco Guglielminotti Trivel, Adjunct Professor of East Asian Art, Turin University. Former Curator and Former Director of MAO Museum of Oriental Art, Turin

Museum: Museo Civico Pier Alessandro Garda, Ivrea, Italy

Acknowledgements: Paola Mantovani (Director of Museo Civico P.A. Garda), Alessia Porpiglia and Luca Diotto (Museum staff). All images © Mariano Dallago. Courtesy of the Museo Civico P.A. Garda in Ivrea.

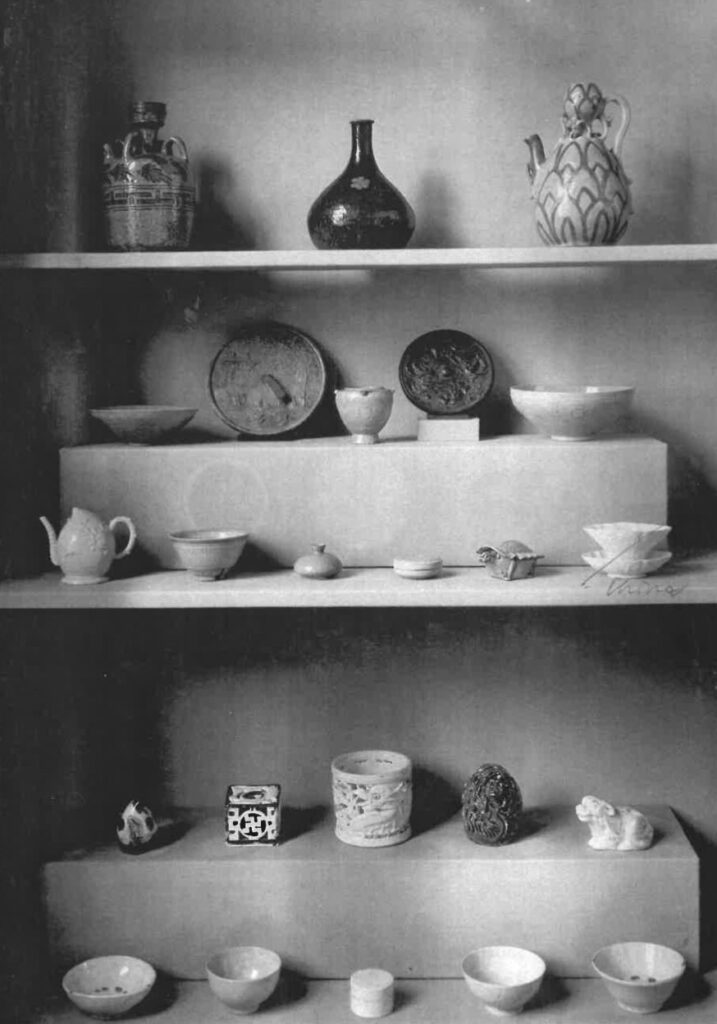

The Civic Museum of Ivrea, located in a major town within the Metropolitan City of Turin, houses an exceptional collection of hundreds of Asian artefacts, primarily Japanese and, to a lesser extent, Chinese. The majority date to the 18th and 19th centuries, with noteworthy examples of lacquerware and bronzes, some of which are outstanding. Less numerous and less studied are ceramics, paintings, and other materials.

The museum’s so-called ‘Oriental’ collection is historically significant and consists of two main groups of artefacts dating back to the 18th and 19th centuries respectively. These were acquired by two prominent citizens of Ivrea. Count Carlo Francesco Baldassarre Perrone (1718–1802) was a military officer and minister with a passion for collecting archaeological artefacts. During his diplomatic postings in Dresden and London, he assembled a collection that, in the late 18th century, became the basis of the so-called “Chinese Museum” at Palazzo Giusiana in Ivrea. This early museum included works from China, America, Madagascar, and India.

The second major figure is Pier Alessandro Garda (1791–1880), a Jacobin politician, revolutionary, and patriot who travelled extensively throughout Europe and South America, collecting predominantly Japanese works. In 1874, Garda donated his collection to the city of Ivrea to establish a museum, which is still named after him. Two years later, he purchased the Perrone collection and also donated it to the city. This combined acquisition formed the nucleus of the first “Japanese and Chinese Museum,” inaugurated at Palazzo Giusiana, with over 720 artefacts. Some additional Asian objects seem to have been incorporated into the museum’s collection by Garda himself before his death.

The collection’s significance lies in its precise terminus ad quem: 1880, the year by which all the objects can be confidently dated. However, its limitations include the difficulty of attributing individual pieces based on historical records and the near-total lack of documentation about their original acquisition. As a result, it is sometimes challenging to determine whether an item originally belonged to Perrone or Garda’s collection. Nonetheless, the collectors’ choice broadly reflects Perrone’s adherence to the 18th-century aesthetic of chinoiserie and Garda’s enthusiasm for 19th-century Japonisme.

In 2024, the Civic Museum hosted a temporary exhibition titled “In Praise of Fragility – Ceramic Art at the P.A. Garda Museum,” marking the 10th anniversary of the museum’s reopening after an extended closure, and coinciding also with the 150th anniversary of Garda’s donation of his Oriental collection. The most substantial section of the exhibition, enriched by national and international loans, focused on East Asia and was curated by the author of this post. The project provided an opportunity to revise some attributions of the museum’s ceramic holdings.

The collection includes about a hundred wares whose general characteristics align with the nature of their acquisitions, as previously noted during internal cataloguing projects: a clear dominance of export-oriented wares and Japanese artefacts (approximately 85%) over Chinese ones.

1.

Seated monkey holding a peach. Porcelain with

famille rose overglaze enamels, h 19 cm. Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province. Qing Dynasty, 18th century. Inv. no. 637,00.

Scimmia seduta con pesca. Porcellana a smalti

famille rose sopra vetrina, h 19 cm. Jingdezhen, Provincia del Jiangxi. Dinastia Qing, XVIII secolo. Inv. 637,00.

The Chinese objects are, on average, older, mostly from the 18th century, with a few 17th – and 19th -century exceptions. Highlights include blanc de Chine figurines from Dehua 德化 and famille rose

Canton porcelain 廣彩 – both highly sought after in European markets. There is also a miniature Yixing

宜興 teapot and several Jingdezhen 景德 porcelains with overglaze enamels, such as a polychrome figurine of a monkey nearly identical to a pair displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (accession no. FE.6A-1978).

The Japanese ceramics, predominantly from 1800 to 1875, consist mainly of Arita ware 有田焼 in the Imari 伊万里 export style. Particularly striking are pairs of large vases and a large dish partially adorned with finely decorated lacquer. Other notable examples include brightly coloured Satsuma 薩摩 and Kutani wares 九谷焼, which were highly favoured by Europeans in the 19th century.

However, the collection also features ceramics less commonly sought after by European collectors. These include Banko wares 萬古焼 from present-day Mie Prefecture, with enamels often applied directly onto the biscuit, as exemplified by the teapot that is shown here. There are also two pieces of the Nanki Otokoyama 南紀男山 tradition, produced by the Sanrakuen kiln 三楽園焼 in Wakayama Prefecture. These feature thick glazes creating a raised effect, such as a bowl with decoration consistent with another example held at the Wakayama Prefectural Museum (id. 538).

2.

Pumpkin-shaped teapot. Stoneware painted with enamels on biscuit, h 8.5 cm. Yokkaichi, Banko ware.

Edo or Meiji period, c. 1825-1875. Inv. no. 452,00.

Teiera a forma di zucca. Grès dipinto a smalti su biscotto, h 8,5 cm. Yokkaichi, produzione Banko. Periodo Edo o Meiji, ca. 1825-1875. Inv. 452,00.

3.

Peony patterned bowl. Porcelain painted with overglaze enamels, d. 19.5 cm. Wakayama, Nanki Otokoyama ware. Edo or Meiji period, c. 1800-1875. Inv. no. 496,00.

Ciotola a motivi peonia. Porcellana dipinta a smalti sopra vetrina, d. 19,5 cm. Wakayama, produzione Nanki Otokoyama. Periodo Edo o Meiji, ca. 1800-1875. Inv. 496,00.

On the opposite end of the spectrum are two refined Hirado 平戸 porcelain pieces from Mikawachi, near Arita, delicately painted under or over the glaze. One standout is a dragon-boat-shaped incense burner, nearly identical to an example at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (accession no. 23.225.327a, b).

4.

Perfume burner in the shape of a dragon boat. Blue and white porcelain with golden highlights, 21.6 x 40.6 x 17.1 cm. Mikawachi, Hirado ware. Edo period, 1st half of the 19th century. Inv. no. 528,00.

Bruciaprofumi a forma di barca drago. Porcellana dipinta di blu sotto vetrina con lumeggiature dorate, 21,6 x 40,6 x 17,1 cm. Mikawachi, produzione Hirado. Periodo Edo, prima metà XIX secolo. Inv. 528,00.

Other wares are represented by only a single piece in the collection. These include a small cloisonné-decorated porcelain cup likely made in Nagoya, two impressed, unglazed porcelain dishes probably from Wakayama in the Kairakuen style 偕楽園焼, and a nice blue-and-white lidded bowl from Fukuoka Prefecture. This last item comes from the kilns of Sue 須恵焼 in Kasuya District, not to be confused with the sueki 須恵器 ceramics of ancient Japan.

5.

Small trays with a decorative character for ‘longevity’. Unglazed porcelain with moulded relief, 11.6 x 15.5 cm each. Wakayama, Kairakuen ware. Edo period, 1st half of the 19th century. Inv. no. 460,01 / 460,02.

Vaschette col carattere decorativo per “longevità”.

Porcellana non invetriata con rilievo stampato, 11,6 x 15,5 cm ciascuna. Wakayama, produzione Kairakuen. Periodo Edo, prima metà XIX secolo.

Inv. 460,01 / 460,02.

6.

Large bowl decorated with peonies. Blue and white porcelain, h 23.5 cm, d. 24.3 cm. Fukuoka, Sue ware.

Edo or Meiji period, c. 1800-1875. Inv. no. 242,00.

Grande ciotola decorata con peonie. Porcellana dipinta di blu sotto vetrina, h 23,5 cm, d. 24,3 cm. Fukuoka, produzione Sue. Periodo Edo o Meiji, ca. 1800-1875. Inv. 242,00.

Further research is needed to establish how and when these less common ceramics entered the museum’s holdings, potentially by identifying connections with similar artefacts dispersed across other European collections.

Bibliography:

Borriello, Maria Paola, Il Museo P.A. Garda. Cronaca e dibattito di fine ‘800, Tipografia Ferraro, Ivrea 1988.

Fragiacomo, Giuseppe, “Un esempio settecentesco di collezionismo in Canavese: il caso del conte Baldassarre Perrone di San Martino”, in Bollettino della Società piemontese di archeologia e belle arti, L, 1998, pp. 313-349.

Guglielminotti Trivel, Marco, “Consistenza e composizione della collezione di ceramiche orientali nel Museo Civico Pier Alessandro Garda / Consistency and composition of the collection of oriental ceramics in the Pier Alessandro Garda Civic Museum”, in Mantovani, Paola et al. (ed.), Elogio della fragilità – Arte ceramica al Museo P.A. Garda (In Praise of Fragility – Ceramic Art at the P.A. Garda Civic Museum), Sagep Editori, Genova 2024, pp. 32-33.

Harada, Kazutoshi – Koyama, Mayumi S. – Peternolli, Giovanni, Kinkô. I Bronzi orientali della collezione Garda, Hever Edizioni, Ivrea 2005.

Koyama, Mayumi S. – Vitali, Fabio A. (ed.), Lacche orientali della collezione Garda, Olivetti, Milano 1994.

Museo Civico Pier Alessandro Garda (ed.), Sezione orientale – Catalogo provvisorio, Rotary Club, Ivrea 1984.

Useful links

Asian collection at the City Museum, Ivrea (Italian only): https://museogardaivrea.promemoriagroup.com/collezione-orientale/

Pair of monkey figures: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1155162/figure-of-monkey-unknown/

Nanki Otokoyama bowl: https://wakayama.museum/hakubutu-wakayama/hakubutu-wakayama-538/

Perfume burner in the shape of a dragon boat: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45949

Ceramiche dell’Asia orientale a Ivrea

di Marco Guglielminotti Trivel, Professore a contratto di arte dell’Asia Orientale, Università di Torino, già conservatore e direttore del MAO Museo d’Arte Orientale, Torino

Museo: Museo Civico Pier Alessandro Garda, Ivrea, Italia

Ringraziamenti: Paola Mantovani (Direttore del Museo Civico P.A. Garda), Alessia Porpiglia e Luca Diotto (staff del Museo). Tutte le immagini © Mariano Dallago. Per gentile concessione del Museo Civico P.A. Garda di Ivrea.

Il Museo Civico di Ivrea, un importante comune situato nella Città Metropolitana di Torino, possiede una collezione pregevole di centinaia di oggetti asiatici, soprattutto giapponesi e in misura minore cinesi, quasi tutti risalenti al XVIII e XIX secolo: notevoli soprattutto le lacche e i bronzi, con alcuni pezzi eccezionali; meno numerose e meno studiate le ceramiche, le pitture e gli altri materiali.

La collezione del Museo, definita storicamente “orientale”, si compone di due nuclei principali, rispettivamente risalenti al ‘700 e all’800, acquisiti da due famosi cittadini eporediesi. Il conte Carlo Francesco Baldassarre Perrone (1718-1802) era un militare e un ministro, già collezionista di reperti archeologici, che ebbe incarichi diplomatici a Dresda e a Londra. Nella seconda metà del ‘700 aprì il cosiddetto “museo Chinese” presso Palazzo Giusiana a Ivrea, che comprendeva opere provenienti dalla Cina, dall’America, dal Madagascar e dall’India.

Pier Alessandro Garda (1791-1880) è stato invece un uomo politico di stampo giacobino, un rivoluzionario e un patriota che aveva vagato per tutta l’Europa e in Sud America, collezionando soprattutto opere giapponesi. Nel 1874 egli donò questa sua collezione alla Città di Ivrea con l’intento di aprire un museo, che in effetti è tuttora a lui intitolato. Due anni dopo acquistò anche la collezione Perrone per donarla alla città, che inaugurò così il primo “Museo Giapponese e Chinese” proprio in Palazzo Giusiana con un totale di oltre 720 oggetti. Qualche altro oggetto asiatico pare che sia stato accorpato alla collezione museale dal Garda stesso prima della morte.

L’importanza di questa collezione è quindi anche quella di avere un terminus ad quem preciso, corrispondente al 1880, per la datazione degli oggetti che la compongono. I limiti consistono invece nella complessa identificazione di un determinato oggetto in base agli archivi storici e nella mancanza pressoché totale di documentazione su dove e quando sia stato acquistato, per cui alle volte è persino difficile stabilire se pertiene originariamente alla raccolta di Perrone o a quella del Garda. Ad ogni buon conto, la scelta collezionistica obbedisce globalmente e pienamente ai canoni della chinoiserie settecentesca seguiti dal Perrone e alla passione per il japonisme ottocentesco abbracciata dal Garda.

Nel 2024 il Museo Civico ha realizzato una mostra temporanea dal titolo “Elogio della fragilità – Arte ceramica al Museo P.A. Garda”, dedicata ai 10 anni dalla riapertura del Museo dopo una prolungata chiusura e che corrisponde anche al 150° anniversario dalla donazione della collezione orientale del Garda. La sezione più consistente della mostra e la più ricca di prestiti nazionali e internazionali è stata sicuramente quella dedicata all’Asia orientale – curata da chi scrive – che ha costituito anche l’occasione per approfondire alcune attribuzioni delle ceramiche in possesso del Museo.

Si tratta di un centinaio di oggetti dalle caratteristiche generali che ci si poteva aspettare considerando la natura delle collezioni, quali erano già emerse nella schedatura interna al Museo: una netta preponderanza di produzioni per l’esportazione e degli oggetti giapponesi (ca. 85%) su quelli cinesi.

Gli oggetti cinesi sono mediamente più antichi, essendo centrati sul XVIII secolo con poche eccezioni seicentesche e ottocentesche. Soprattutto statuine blanc de Chine da Dehua 德化 e vasellame famille rose del tipo ‘porcellana di Canton’ 廣彩 – tra le produzioni più ricercate dal mercato europeo – ma anche una piccola teiera Yixing 宜興 e qualche porcellana dipinta a smalti sopravetrina da Jingdezhen 景德鎮. A titolo di esempio, una statuina policroma di scimmia che è quasi identica a una coppia esposta nel Victoria & Albert Museum a Londra (accession no. FE.6A-1978).

Per quanto riguarda la parte giapponese, che è per lo più databile tra il 1800 e il 1875, come c’era da aspettarsi la maggioranza delle ceramiche è di produzione Arita 有田焼 in stile Imari 伊万里 per l’esportazione. Spiccano su tutti delle coppie di grandi vasi e un grande piatto, parzialmente ricoperti di lacca finemente decorata. Bene attestate sono anche altre due produzioni caratterizzate da intense policromie che incontravano il favore degli europei nell’Ottocento: Satsuma 薩摩 e Kutani 九谷.

Eccezionalmente, anche qualche produzione meno nota che generalmente non era ricercata dai collezionisti europei trova posto nella collezione. Per esempio la Banko 萬古, prodotta nell’attuale prefettura di Mie, che è sovente smaltata direttamente sul biscotto come la teiera qui illustrata. Oppure la Nanki Otokoyama 南紀男山, prodotta nella prefettura di Wakayama dalla fornace Sanrakuen 三楽園焼, della quale si sono identificati due esemplari. Tali ceramiche sono invece completamente ricoperte di smalti spessi, che danno un effetto quasi a rilievo. La decorazione della ciotola è consistente con un’altra a fondo piatto conservata nel Museo della Prefettura di Wakayama (id. 538), seppure la forma e la tavolozza dei colori siano diverse. All’estremo opposto troviamo un paio di raffinate porcellane di tipo Hirado 平戸 da Mikawachi, presso Arita, dipinte delicatamente sotto e/o sopra vetrina. Identifico con tale produzione un bruciaprofumi a forma di “Barca Drago”, che troviamo quasi identico nelle collezioni del Metropolitan Museum of Art di New York (accession no. 23.225.327a, b).

Infine, altre produzioni sono rappresentate in collezione da un solo oggetto. Abbiamo un bicchierino di porcellana decorata esternamente a cloisonné, probabilmente prodotto a Nagoya; due vaschette da portata in porcellana non invetriata e decorata a stampo che provengono quasi sicuramente da Wakayama, in stile Kairakuen 偕楽園焼; una bella ciotola con coperchio di porcellana “bianca e blu” prodotta nella prefettura di Fukuoka. Quest’ultima proviene dalle fornaci di Sue 須恵焼, una cittadina nel distretto di Kasuya – da non confondersi con la tipologia ceramica sueki 須恵器 del Giappone antico.

Su come e quando tali ceramiche particolari siano pervenute nelle collezioni del Museo di Ivrea è un tema da approfondire, magari cercando connessioni con oggetti delle stesse produzioni “minori” sparse negli altri musei europei.